This porting is free but needs your support to sustain its development. There are lots of desirable new features and maintenance to do. If you are an individual using dear imgui, please consider donating via Patreon or PayPal. If your company is using dear imgui, please consider financial support (e.g. sponsoring a few weeks/months of development)

Monthly donations via Patreon:

This is the Kotlin port of dear imgui (AKA ImGui), a bloat-free graphical user interface library in C++. It outputs optimized vertex buffers that you can render anytime in your 3D-pipeline enabled application. It is fast, portable, renderer agnostic and self-contained (few dependencies).

Dear ImGui is designed to enable fast iteration and empower programmers to create content creation tools and visualization/ debug tools (as opposed to UI for the average end-user). It favors simplicity and productivity toward this goal, and thus lacks certain features normally found in more high-level libraries.

Dear ImGui is particularly suited to integration in realtime 3D applications, fullscreen applications, embedded applications, games, or any applications on consoles platforms where operating system features are non-standard.

Dear ImGui is self-contained within a few files that you can easily copy and compile into your application/engine.

Your code passes mouse/keyboard inputs and settings to Dear ImGui (see example applications for more details). After ImGui is setup, you can use it like in this example:

var f = 0f

with(ImGui) {

text("Hello, world %d", 123)

button("OK"){

// react

}

inputText("string", buf)

sliderFloat("float", ::f, 0f, 1f)

}ImGui imgui = ImGui.INSTANCE;

float[] f = {0f};

imgui.text("Hello, world %d", 123);

if(imgui.button("OK")) {

// react

}

imgui.inputText("string", buf);

imgui.sliderFloat("float", f, 0f, 1f);Dear ImGui outputs vertex buffers and simple command-lists that you can render in your application. The number of draw calls and state changes is typically very small. Because it doesn't know or touch graphics state directly, you can call ImGui commands anywhere in your code (e.g. in the middle of a running algorithm, or in the middle of your own rendering process). Refer to the sample applications in the examples/ folder for instructions on how to integrate ImGui with your existing codebase.

A common misunderstanding is to think that immediate mode gui == immediate mode rendering, which usually implies hammering your driver/GPU with a bunch of inefficient draw calls and state changes, as the gui functions are called by the user. This is NOT what Dear ImGui does. Dear ImGui outputs vertex buffers and a small list of draw calls batches. It never touches your GPU directly. The draw call batches are decently optimal and you can render them later, in your app or even remotely.

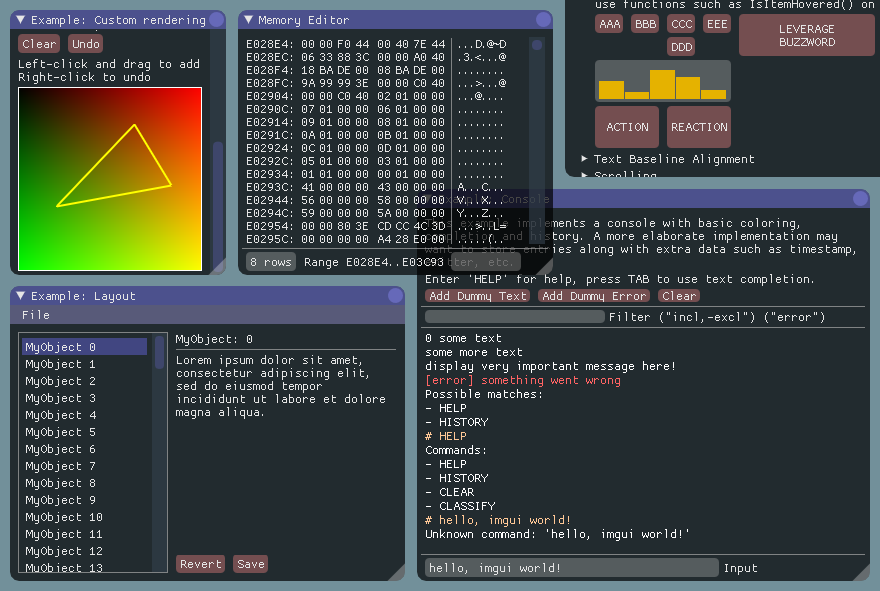

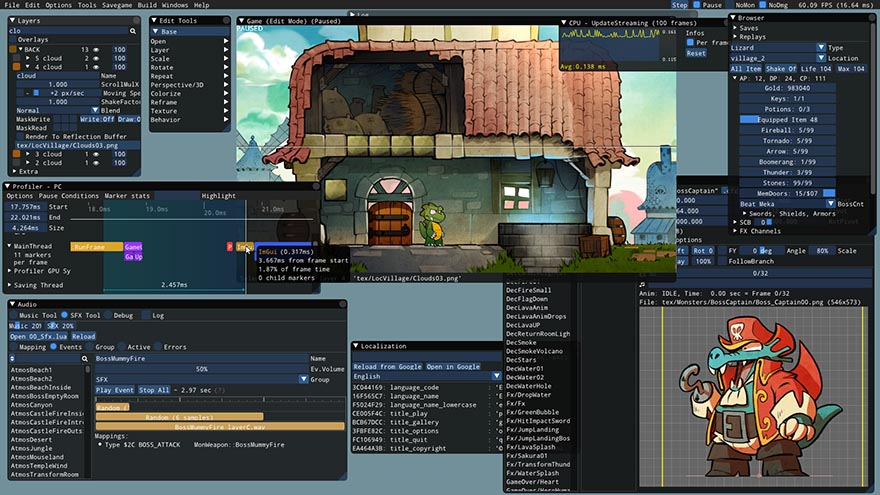

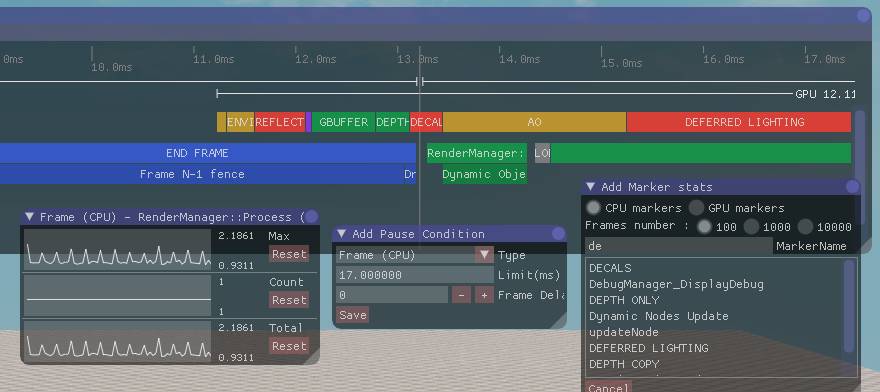

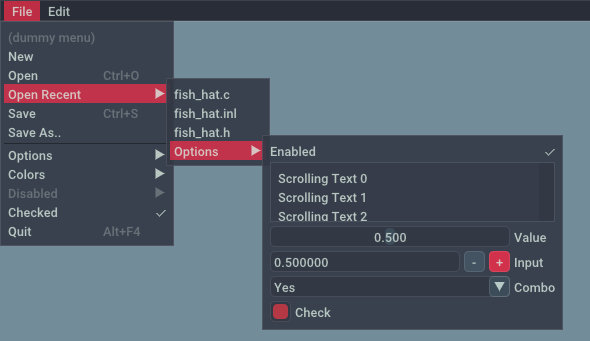

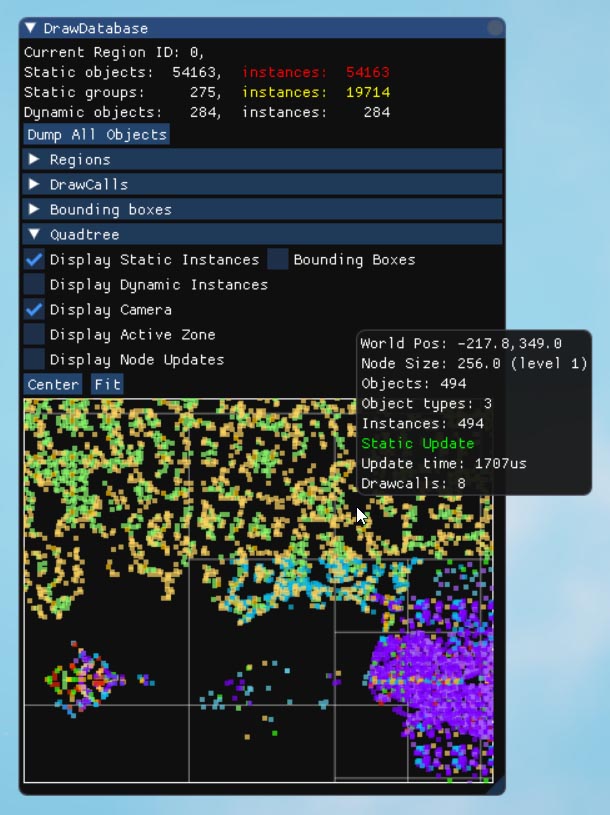

Dear ImGui allows you create elaborate tools as well as very short-lived ones. On the extreme side of short-liveness: using the Edit&Continue feature of modern compilers you can add a few widgets to tweaks variables while your application is running, and remove the code a minute later! ImGui is not just for tweaking values. You can use it to trace a running algorithm by just emitting text commands. You can use it along with your own reflection data to browse your dataset live. You can use it to expose the internals of a subsystem in your engine, to create a logger, an inspection tool, a profiler, a debugger, an entire game making editor/framework, etc.

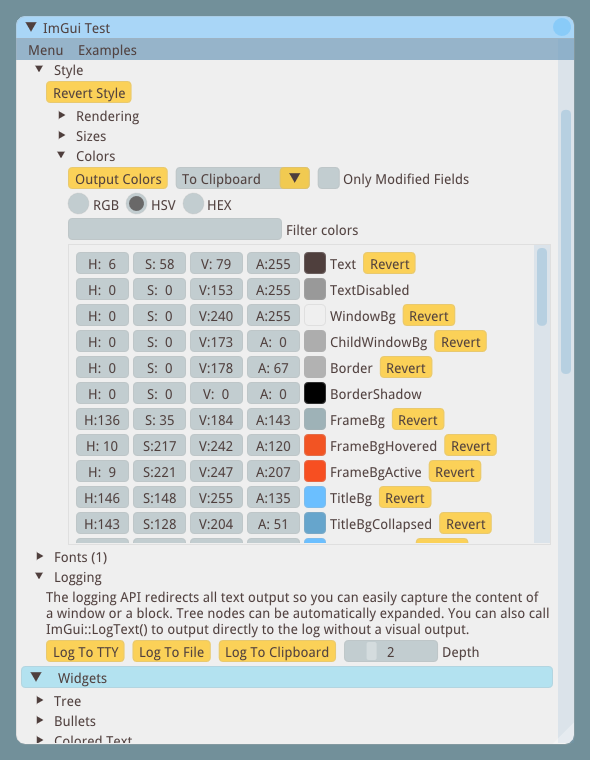

User screenshots:

Gallery Part 1 (Feb 2015 to Feb 2016)

Gallery Part 2 (Feb 2016 to Aug 2016)

Gallery Part 3 (Aug 2016 to Jan 2017)

Gallery Part 4 (Jan 2017 to Aug 2017)

Gallery Part 5 (Aug 2017 onward)

Also see the Mega screenshots for an idea of the available features.

ImGui supports also other languages, such as japanese, initiliazed here as:

IO.fonts.addFontFromFileTTF("extraFonts/ArialUni.ttf", 18f, glyphRanges = IO.fonts.glyphRangesJapanese)!!or here

Font font = io.getFonts().addFontFromFileTTF("extraFonts/ArialUni.ttf", 18f, new FontConfig(), io.getFonts().getGlyphRangesJapanese());

assert (font != null);The Immediate Mode GUI paradigm may at first appear unusual to some users. This is mainly because "Retained Mode" GUIs have been so widespread and predominant. The following links can give you a better understanding about how Immediate Mode GUIs works.

- Johannes 'johno' Norneby's article.

- A presentation by Rickard Gustafsson and Johannes Algelind.

- Jari Komppa's tutorial on building an ImGui library.

- Casey Muratori's original video that popularized the concept.

- Nicolas Guillemot's CppCon'16 flashtalk about Dear ImGui.

- Thierry Excoffier's Zero Memory Widget.

ImGui does not impose any platform specific dependency. Therefor users must specify runtime dependencies themselves. This should be done with great care to ensure that the dependencies versions do not conflict.

Using Gradle with the following workaround is recommended to keep the manual maintenance cost low.

import org.gradle.internal.os.OperatingSystem

repositories {

...

maven { url 'https://jitpack.io' }

}

dependencies {

compile 'com.github.kotlin-graphics:imgui:-SNAPSHOT'

switch ( OperatingSystem.current() ) {

case OperatingSystem.WINDOWS:

ext.lwjglNatives = "natives-windows"

break

case OperatingSystem.LINUX:

ext.lwjglNatives = "natives-linux"

break

case OperatingSystem.MAC_OS:

ext.lwjglNatives = "natives-macos"

break

}

// Look up which modules and versions of LWJGL are required and add setup the approriate natives.

configurations.compile.resolvedConfiguration.getResolvedArtifacts().forEach {

if (it.moduleVersion.id.group == "org.lwjgl") {

runtime "org.lwjgl:${it.moduleVersion.id.name}:${it.moduleVersion.id.version}:${lwjglNatives}"

}

}

}Please refer to the wiki for a more detailed guide and for other systems (such as Maven, Sbt or Leiningen).

On the initiative to Catvert, ImGui plays now nice also with LibGdx.

Simply follow this short wiki on how to set it up.

90% ported

Things to notice:

-

text inputs handling, weak/bugged

-

foreign languages support: at the moment tested shortly only japanese with IME support on Windows, not yet fully robust and tested

-

other fonts Shortly tested

-

and few other small things which escaped the demo checking

I'm looking for feedbacks to report and get fixed as much bugs as possible, don't hesitate to contribute (wiki, code, screenshots, suggestions, whatever)

To check what has been already ported and working, simply run one of the tests in Kotlin:

or in Java:

You should refer to those also to learn how to use the imgui library.

Ps: DEBUG = false to turn off debugs println()

- copy/cut/undo/redo text

- text filters

Developed by Omar Cornut and every direct or indirect contributors to the GitHub. The early version of this library was developed with the support of Media Molecule and first used internally on the game Tearaway.

Omar first discovered imgui principles at Q-Games where Atman had dropped his own simple imgui implementation in the codebase, which Omar spent quite some time improving and thinking about. It turned out that Atman was exposed to the concept directly by working with Casey. When Omar moved to Media Molecule he rewrote a new library trying to overcome the flaws and limitations of the first one he's worked with. It became this library and since then Omar has spent an unreasonable amount of time iterating on it.

Embeds ProggyClean.ttf font by Tristan Grimmer (MIT license).

Embeds stb_textedit.h, stb_truetype.h, stb_rectpack.h by Sean Barrett (public domain).

Inspiration, feedback, and testing for early versions: Casey Muratori, Atman Binstock, Mikko Mononen, Emmanuel Briney, Stefan Kamoda, Anton Mikhailov, Matt Willis. And everybody posting feedback, questions and patches on the GitHub.