You can also find all 40 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - Concurrency

Concurrency describes a system's capability to deal with a large number of tasks that might start, run, and complete independently of each other. This is the hallmark of multi-tasking operating systems.

In contrast, parallelism revolves around performing multiple tasks simultaneously. Such systems often leverage multi-core processors.

Concurrency and parallelism can coexist, but they don't necessarily require each other. A program can be:

- Concurrenct but not parallel: e.g., a single-core processor multitasking

- Parallel but not concurrent: e.g., divided tasks distributed across multiple cores

- Concurrency: Achieved through contextual task-switching. For example, using time slicing or handcrafted interruption points in the code.

- Parallelism: Achieved when the system can truly execute multiple tasks in parallel, typically in the context of multi-core systems.

In a concurrent environment, multiple threads or tasks can access shared resources simultaneously. Without proper handling, this can lead to race conditions, corrupting the data.

Ensuring thread-safety involves employing strategies like:

- Locking

- Atomic Operations

- Transactional Memory

- Immutable Data

- Message Passing

Here is the Python code:

import threading

# Two independent tasks that can run concurrently

def task_1():

print("Starting Task 1")

# Simulate some time-consuming work

for i in range(10000000):

pass

print("Completed Task 1")

def task_2():

print("Starting Task 2")

# Simulate some time-consuming work

for i in range(10000000):

pass

print("Completed Task 2")

# Create and start thread objects to achieve concurrency on a single-core system

thread1 = threading.Thread(target=task_1)

thread2 = threading.Thread(target=task_2)

thread1.start()

thread2.start()

# In a multi-core system, the tasks can also run in parallel

# To emulate this behavior on a single-core system, we can use:

# Python's "concurrent.futures" module.

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

# Create a thread pool

executor = ThreadPoolExecutor()

# Submit the tasks for parallel execution

task1_future = executor.submit(task_1)

task2_future = executor.submit(task_2)

# Proper cleanup

executor.shutdown()Race conditions arise in multithreaded or distributed systems when the final outcome depends on the sequence or timing of thread or process execution, which in turn may lead to inconsistent or unexpected behavior.

- Shared Resources: For a race condition to occur, threads or processes must access and potentially alter shared resources or data.

- Non-Atomic Operations: Processes might rely on multiple operations, such as read-modify-write operations, which can be interrupted between steps.

- Network Communication: In distributed systems, delays in network communication can lead to race conditions.

- I/O Operations: File or database writes can lead to race conditions if data is not consistently updated.

- Split I/O: Using multiple modules for I/O can introduce the possibility of race conditions.

Consider the following Python code:

Here is the Python code:

import threading

# Shared resource

counter = 0

def increment_counter():

global counter

for _ in range(1000000):

counter += 1

# Create threads

thread1 = threading.Thread(target=increment_counter)

thread2 = threading.Thread(target=increment_counter)

# Start threads

thread1.start()

thread2.start()

# Wait for both threads to finish

thread1.join()

thread2.join()

# Expected value (though uncertain due to the race condition)

print(f"Expected: 2000000, Actual: {counter}")- Synchronization: Techniques such as locks, semaphores, and barriers ensure exclusive access to shared resources, thus preventing race conditions.

- Atomic Operations: Many programming languages and libraries provide primitive operations that are atomic, ensuring they are not interrupted.

- Use of Immutable Data: In some scenarios, using immutable, or read-only data can help avoid race conditions.

- Order Encapsulation: Establish a clear order in which methods or operations should execute to ensure consistency.

- Parallel Programming Best Practices: Staying updated with best practices in parallel programming and adopting them can help in identifying and mitigating race conditions.

In concurrent programming, a critical section is a part of the code where shared resources are being accessed by multiple threads. It's essential to manage access to these sections to prevent inconsistencies and ensure data integrity.

Synchronization techniques, such as locks or semaphores, are used to regulate access to critical sections.

- Data Integrity: Guarantee that shared resources are consistent and not left in intermediate states.

- Efficiency: Ensure that non-critical tasks can be executed concurrently for optimal resource utilization.

- Independence: Encourage thread independence within non-critical sections.

- Deadlocks: Occur when two or more threads are blocked indefinitely, waiting for each other.

- Live Locks: Threads are both active but unable to progress.

- Resource Starvation: One or more threads are unable to access the critical section.

Locks, the most frequently used mechanism, help coordinate access to shared resources by employing locks or flags. If a thread tries to enter a critical section and a lock is already set, the thread is suspended until the lock is released.

Semaphores enable more sophisticated control over access to resources by managing a digital counter referred to as the "semaphore value". Threads can acquire or release "permits" to interact with shared resources. The most common type, a binary semaphore, acts much like a lock.

While critical sections are crucial for maintaining data consistency, excessive use of locks can lead to performance degradation due to synchronization overheads.

It's a balancing act: efficient programs aim to minimize the time spent within critical sections and optimize the number of lock/unlock operations.

Operating Systems prevent race conditions and ensure mutual exclusion using various mechanisms such as locking, timing, and hardware support.

-

Locking: Operating systems use locks, accessed through primitives like

lock()andunlock(), to restrict concurrent access to shared resources. -

Timing: Time delay techniques, such as busy-wait loops, help coordinate access among processes.

-

Hardware Support: Modern CPUs rely on hardware features like atomic instructions and caching strategies for efficient synchronization.

Here is the C++ code:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

std::mutex resourceMutex;

void processA() {

resourceMutex.lock();

std::cout << "Process A is accessing the shared resource.\n";

resourceMutex.unlock();

}

void processB() {

resourceMutex.lock();

std::cout << "Process B is accessing the shared resource.\n";

resourceMutex.unlock();

}

int main() {

std::thread t1(processA);

std::thread t2(processB);

t1.join();

t2.join();

return 0;

}In this code, both processA and processB attempt to lock the resourceMutex before accessing the shared resource. If the mutex is already locked by the other process, the calling process will be blocked until the mutex is released, ensuring mutual exclusion.

Atomicity in concurrency refers to operations that appear to happen indivisibly. An operation is either fully executed or not at all, meaning that concurrent operations do not observe intermediary states, thereby avoiding data inconsistency.

-

Multi-Step State Transitions: Complex transformations across multiple interdependent data points, like when transferring money between bank accounts or during a database commit or rollback.

-

Shared Resource Modifications: Consistent, reliable updates to data structures, arrays, lists, and databases that are accessed and modified by multiple threads simultaneously.

Standard operations on most data types (e.g., integers, longs, pointers).

An example of a non-atomic operation is an integer ++ operation in many programming languages. It involves three steps: read the current value, increment it, and store it back. During multi-threaded access, another thread might have modified the value of the integer between the read and write steps, leading to a data inconsistency.

-

Consistency: Ensures that an operation either completes as a whole or does not take effect at all.

-

Isolation: Guarantees that the operation occurs independently of any other concurrent operations.

-

Durability: Maintains the integrity of data, especially during failure or interruption, to prevent data corruption.

- Hardware Influence: Some hardware architectures might provide implicit atomicity for certain types of operations or memory locations, aiding in thread and data safety.

- Software Relying on Atomicity: Concurrency control mechanisms in multithreaded applications, such as locks, semaphores, or certain data structures (e.g., atomic variables, compare-and-swap mechanisms), depend on the notion of operation atomicity for consistency and integrity.

- Data Integrity: Ensuring data integrity within a multi-threaded environment is a fundamental requirement. Both multi-threaded locks and atomic operations play vital roles.

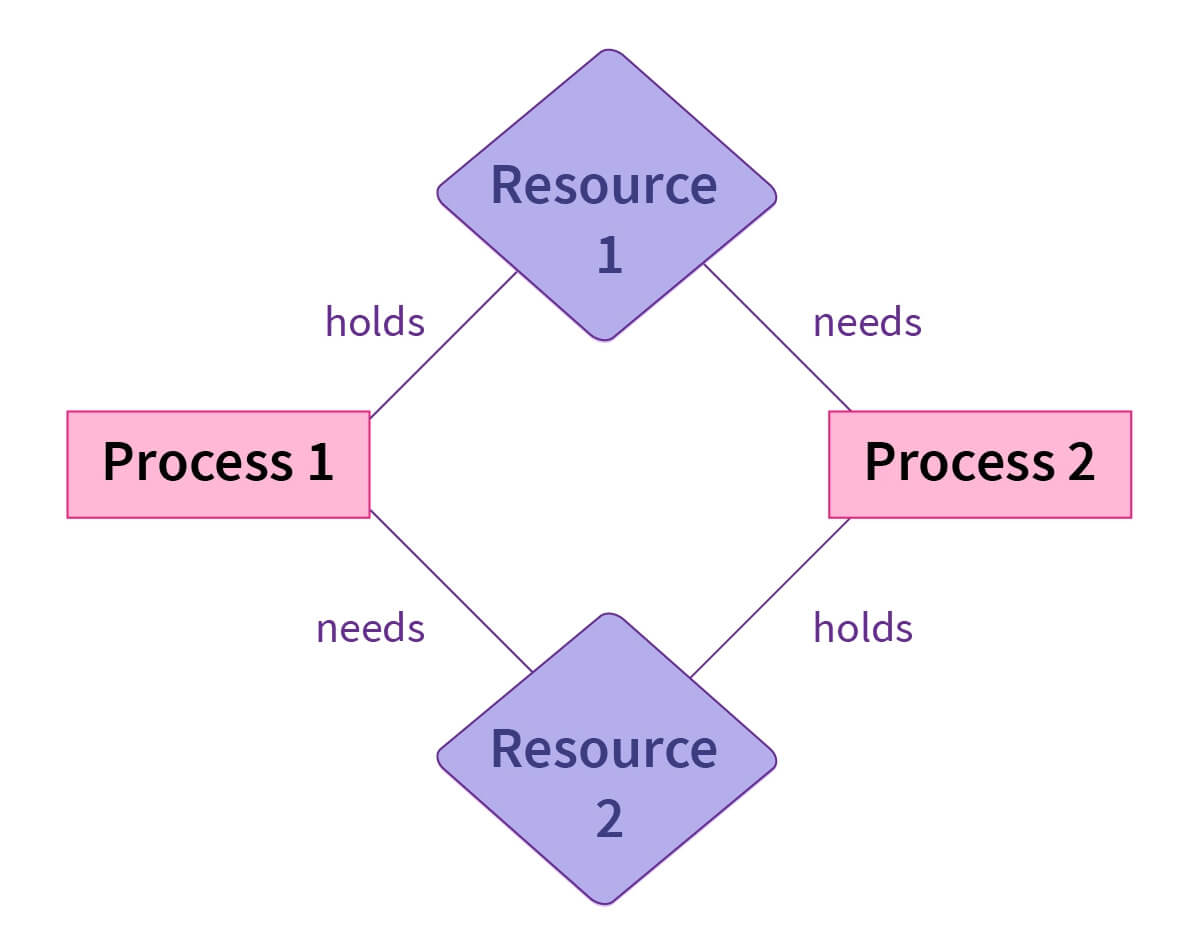

Deadlocks in concurrent systems happen when two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other.

Common resources leading to deadlock are:

- Synchronized Data

- Memory

- Files

- Or Hardware Devices

Let's take a look at some common deadlock scenarios and their solutions:

-

Mutual Exclusion

Problem: Resource can only be accessed by one thread at a time.

Solution: Relax this requirement if possible. -

Hold and Wait

Problem: Threads holding resources are waiting for others, leading to deadlock.

Solution: Introduce a mechanism ensuring a thread doesn't hold resources while waiting for more. -

No Preemption

Problem: Resources are not preemptible, meaning a thread might hold a resource indefinitely.

Solution: Introduce a mechanism for resource preemption when necessary. -

Circular Wait

Problem: Threads form a circular chain of resource dependencies.

Solution: Order your resource requests or use a mechanism to detect and break circular wait chains.

Here is the Java code:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

public class DeadlockExample {

private Lock lock1 = new ReentrantLock();

private Lock lock2 = new ReentrantLock();

public void method1() {

lock1.lock();

System.out.println("Method1: Acquired lock1");

// Intentional sleep to exaggerate deadlock scenario

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

lock2.lock();

System.out.println("Method1: Acquired lock2");

lock1.unlock();

lock2.unlock();

}

public void method2() {

lock2.lock();

System.out.println("Method2: Acquired lock2");

lock1.lock();

System.out.println("Method2: Acquired lock1");

lock1.unlock();

lock2.unlock();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

DeadlockExample example = new DeadlockExample();

Thread t1 = new Thread(example::method1);

Thread t2 = new Thread(example::method2);

t1.start();

t2.start();

}

}Both livelocks and deadlocks represent unwanted states in concurrent systems, but they differ in behavior and resolution methods.

-

Deadlock: This state occurs when multiple processes are each waiting for the others to release resources, resulting in a standstill. Traditional deadlock detection may not always work due to circular dependencies in resource acquisition.

-

Livelock: In a livelock, processes are active but make no progress due to repeated, cyclic interaction. This can resemble a polite dance, where participants continuously step aside for one another.

-

Deadlock: Two threads need access to resources A and B, but each is holding one resource and waiting for the other. This results in a standstill; neither thread can continue.

-

Livelock: Two threads continuously yield resources, thinking they are trying to be cooperative. However, this back-and-forth dance does not lead to any progress.

Here is the Python code:

import threading

def worker1(lock1, lock2):

while True:

print("Worker 1: Trying lock 1")

with lock1:

print("Worker 1: Acquired lock 1")

print("Worker 1: Releasing lock 1")

print("Worker 1: Trying to acquire lock 2")

with lock2:

print("Worker 1: Acquired both locks!")

print("Worker 1: Releasing lock 2")

def worker2(lock1, lock2):

while True:

print("Worker 2: Trying lock 2")

with lock2:

print("Worker 2: Acquired lock 2")

print("Worker 2: Releasing lock 2")

print("Worker 2: Trying to acquire lock 1")

with lock1:

print("Worker 2: Acquired both locks!")

print("Worker 2: Releasing lock 1")

lock1 = threading.Lock()

lock2 = threading.Lock()

t1 = threading.Thread(target=worker1, args=(lock1, lock2))

t2 = threading.Thread(target=worker2, args=(lock1, lock2))

t1.start()

t2.start()8. Can you explain the producer-consumer problem and how can it be addressed using concurrency mechanisms?

The Producer-Consumer Problem represents a classic synchronization challenge in computer science. It deals with an active producer and a consumer, both of whom access a shared, limited-size buffer.

- Producer: Generates data items and places them in the buffer.

- Consumer: Removes items from the buffer.

- Buffer: Acts as a shared resource between the producer and consumer.

- Data Integrity: Making sure the producer doesn't add items to a full buffer, and the consumer doesn't retrieve from an empty one.

- Synchronization: Coordinating the actions of the producer and the consumer to prevent issues such as data corruption or deadlock.

Several strategies use concurrency mechanisms to address the Producer-Consumer Problem:

-

Locks/Mutexes: Classic methods that utilize mutual exclusion.

-

Condition Variables: Used in conjunction with locks and mutexes for more robust synchronization. These ensure threads are notified when a certain condition becomes true.

-

Semaphores: A generalization of locks/mutexes that can regulate access to a shared resource using a counter.

-

Deadlock: A scenario where both the producer and consumer are head-locked, resulting in a system standstill.

- A common approach to resolving deadlock involves using timed conditional waits, so a thread does not wait indefinitely without knowing if a situation will change.

-

Starvation: A potential risk when a thread, either the producer or consumer, is not granted access to the shared resource despite being ready.

- Solutions include ensuring that waiting threads are served in a fair order or through mechanisms like the "turn" variable.

-

Synchronization: Ensuring actions are well-coordinated can be achieved through a combination of locks, condition variables, and semaphores.

-

Data Integrity: It is essential to make sure the buffer is accessed in a thread-safe manner.

- A practical way to achieve this would be to use locks or other synchronization mechanism for controlled access to the buffer, ensuring data integrity.

-

Performance Concerns: An inefficient design can lead to issues like overproduction or redundant waiting. This can result in poor resource utilization or increased latencies.

Here is the Python code:

from threading import Thread, Lock, Condition

import time

from queue import Queue

# initialize buffer, shared by producer and consumer

buffer = Queue(maxsize=10)

# lock for controlled buffer access

lock = Lock()

# condition to signal when the buffer is not full/empty

buffer_not_full = Condition(lock)

buffer_not_empty = Condition(lock)

class Producer(Thread):

def run(self):

for i in range(100):

with buffer_not_full:

while buffer.full():

buffer_not_full.wait()

with lock:

buffer.put(i)

print(f"Produced: {i}")

buffer_not_empty.notify()

class Consumer(Thread):

def run(self):

for i in range(100):

with buffer_not_empty:

while buffer.empty():

buffer_not_empty.wait()

with lock:

item = buffer.get()

print(f"Consumed: {item}")

buffer_not_full.notify()

# start producer and consumer threads

producer = Producer()

consumer = Consumer()

producer.start()

consumer.start()Processes and threads are fundamental to multi-tasking and concurrency in computational systems. They operate at different levels - process at the operating system level and thread at the application level.

-

Unit of Scheduling - Process is the unit of CPU time, whereas a thread is a lightweight process that can be scheduled for CPU time.

-

Memory - Each process has its private memory space, while all threads within a process share the same memory space, providing faster communication.

-

Creation Overhead - Processes are heavier to create, with more startup overhead like memory allocation and initialization. Threads are lightweight and are created quickly.

-

Communication and Synchronization - Processes communicate via inter-process communication (IPC) tools such as pipes and sockets. In contrast, threads can communicate more directly through shared memory and are typically synchronized using techniques such as locks.

-

Fault Isolation - Processes are more resilient to faults as an issue in one process won't affect others. Threads, being part of the same process, can potentially cause all of them to crash due to memory and resource sharing.

-

Programming Complexity - Threads within a process share resources and need careful management, making them suitable for efficiency gains in certain scenarios. Processes are more isolated and easier to manage, but the communication and context switching can be more complicated, leading to potential inefficiencies in resource use.

Threads are units of execution within a process. They allow for concurrent tasks and share resources like memory and file handles. Operating systems in use today employ a range of thread management models such as Many to Many, One to One, and Many to One.

In this model, multiple threads from a single process are mapped to multiple kernel threads, offering the best flexibility in terms of scheduling. However, it incurs considerable overhead since both the library and the kernel need to manage threads.

Each thread is affiliated with a separate kernel thread, ensuring the parallelism of the tasks. It is more resource-intensive because of additional overhead and kernel involvement.

This model maps multiple user-level threads to a single kernel thread, providing efficient management at the cost of limited parallelism due to potential blocking.

These are libraries associated with a specific programming language or software environment, managing threads entirely in user-space, without kernel support. They can be one of:

- Green Threads: These tend to be relatively lightweight and offer features like cooperative multi-threading.

- POSIX Threads: Commonly used in Unix-like systems, they execute system calls to the kernel for certain thread operations.

Some operating systems offer built-in support for threads at the kernel level, allowing for more direct control and enhanced performance.

In recent years, a hybrid approach has emerged, combining user-level and kernel-level thread management, aiming to achieve both flexibility and performance.

Here is the Python code to create threads using the threading module:

import threading

def task():

print("Running in thread", threading.get_ident())

thread1 = threading.Thread(target=task)

thread2 = threading.Thread(target=task)

thread1.start()

thread2.start()In this example, two threads are created using the Thread class, with each executing the task function. The start method is invoked to initiate their execution.

A thread pool is a mechanism to manage and limit the number of active threads executing tasks in an application.

-

Improved Performance: Thread pools, by reusing threads for multiple tasks, eliminate the overhead of thread creation and destruction. This strategy improves application responsiveness and performance.

-

Resource Management: The invocation of too many threads in a short time can clutter system resources. A thread pool resolves this issue by regulating the count of active threads, ensuring optimal resource utilization.

-

Convenience and Readability: Instead of managing thread lifecycles manually, developers can submit tasks to a thread pool, which takes charge of execution.

-

Asynchronous Processing: Provides a means to execute tasks in the background, typical of web servers, graphical user interfaces, and more.

-

Batch Processing: Useful for executing a series of tasks or data operations, for example, in data processing applications.

-

Load Management: Enables throttling the execution of tasks during periods of high system load or to control resource consumption.

Here is the Java code:

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

public class ThreadPoolExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Creates a thread pool of up to 5 threads

ExecutorService executor = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(5);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

final int taskId = i;

// Submits tasks to the thread pool

executor.submit(() -> System.out.println("Task " + taskId + " executed by thread: " + Thread.currentThread().getName()));

}

// Shuts down the thread pool

executor.shutdown();

}

}Let's understand what is a context switch and its role in concurrency.

A context switch is the process of saving the state of a running thread or process and restoring the state of another one so that both can appear to run simultaneously.

Various events can trigger a context switch:

- A thread voluntarily yielding the CPU, such as when an I/O operation is being performed.

- A higher-priority thread becoming ready to run.

- The OS employing preemption of a thread due to time slicing, where a time quantum is reached.

The CPU Scheduler manages how CPU cores are assigned to threads or processes. It's responsible for deciding and implementing the switching of execution contexts quickly and efficiently.

Here is the Java code:

public class ContextSwitchExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread t1 = new Thread(new MyTask("Task 1", 50));

Thread t2 = new Thread(new MyTask("Task 2", 100));

t1.start();

t2.start();

try {

t1.join();

t2.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

System.out.println("An error occurred in thread execution.");

}

}

}

class MyTask implements Runnable {

private String name;

private int delay;

public MyTask(String name, int delay) {

this.name = name;

this.delay = delay;

}

@Override

public void run() {

System.out.println("Task " + name + " is running.");

try {

Thread.sleep(delay);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

System.out.println("Task " + name + " was interrupted.");

}

System.out.println("Task " + name + " completed.");

}

}Thread size can significantly impact system performance in various ways. Here, we look at the pros and cons of many small threads versus few large threads.

- Benefits:

- Resource Segregation: Ideal for isolating resources, enabling efficient resource management and security measures.

- Work Granularity: Suitable for fine-grained tasks and optimized performance on multi-core systems.

- Responsiveness: Ensures swift system responsiveness due to minimized task queuing and context-switching.

- Disadvantages:

- Thread Overhead: Coordinating many threads can result in increased management overhead.

- Latency Impact: Short tasks might be delayed by thread scheduling, affecting their response times.

- Latch Resource Handling: Numerous threads can lead to latch resource contention, unwarranted locks, or excessive memory usage.

- Benefits:

- Lower Overhead: Eases computational and memory management due to a reduced number of threads.

- Task Prioritization: Streamlines critical task execution and ensures prioritized focus.

- Resource Efficiency: More effective use of system resources like CPU caches and memory.

- Disadvantages:

- Potential Workstarvation: Lengthy operations might monopolize thread execution, leading to non-responsiveness.

- Complexity in Design: Demanding to intricately manage inter-thread communication and resource sharing in such a setup.

- Task-Dependent Selection: Tailor thread size to the nature of the tasks; use many small threads for short-lived tasks and few large threads for long-running ones.

- Dynamic Adaption: Employ strategies like dynamic thread pools, adjusting thread count based on system load, and task arrival rate for an optimal balance.

- Distributed Workload: For larger programs, consider using a mix of small and large threads to distribute the computational load more evenly.

In computer science, a mutex (short for "mutual exclusion") is a synchronization mechanism that ensures only one thread can access a shared resource at a time.

A mutex employs a simple lock/unlock interface:

-

Lock: When a thread wants to access a shared resource, it first locks the mutex. If the mutex is already locked by another thread, the current thread is either blocked or can choose to perform other actions, such as waiting in a loop or executing different code paths.

-

Unlock: After a thread is done with the resource, it unlocks the mutex, making it available for other threads.

This two-step process ensures that access to shared resources is properly controlled, and race conditions are avoided.

-

Reentrant Mutex: Also known as a recursive mutex, it allows a thread to re-lock a mutex it already locked, avoiding a deadlock. However, the mutex must be unlocked a corresponding number of times to make it available to other threads.

-

Timed Mutex: Indicates the maximum time a thread should be blocked while waiting for a mutex. If the waiting time exceeds this limit, the calling thread continues execution without the mutex and performs other actions.

-

Try Lock: A non-blocking version of lock. If the mutex is available, it's locked, and the calling thread continues execution. If not, the thread doesn't wait and can execute other tasks or try again later.

-

Deadlocks: This occurs when two or more threads are waiting for each other to release resources, leading to a standstill. Resource acquisition in a program should be designed in such a way that a deadlock never occurs.

-

Priority Inversion: A lower-priority task holds a mutex needed by a higher-priority task, causing the higher-priority task to wait longer for the resource.

-

Lock Contention: If a mutex is frequently accessed by multiple threads, it can lead to lock contention, causing threads to wait unnecessarily.

-

Performance Impact: Repeated locking and unlocking can add overhead, especially if the critical section is small and the contention is high.

Mutexes and semaphores are synchronization mechanisms fundamental to multi-threading. Here is a detailed comparison:

- Ownership: A mutex provides exclusive ownership, ensuring only the thread that locks it can unlock it.

- State: Binary in nature, a mutex is either locked or unlocked.

- Ownership: No thread has exclusive ownership of a semaphore. Any thread can signal it, which can be useful in various synchronization scenarios.

- State: Analog, representing a count of available resources or a specified numerical value.

- Mutex: Uses

lockandunlockoperations. - Semaphore: Employs

waitandsignal(orpost) operations.

- Lock: If available, it locks the mutex; if not, the calling thread waits.

- Unlock: Releases the mutex, potentially allowing another thread to acquire it.

- Wait: If the semaphore's count is non-zero, it decrements the count and proceeds. If the count is zero, it waits.

- Signal: Increments the semaphore's count.

- Guarded Access: Useful when a resource, say a file or data structure, must be exclusively owned by a single thread at a time.

-

Resource Management: When managing a finite set of resources, semaphores are apt.

For instance, if there are ten spaces in a parking lot, a semaphore initialized to ten can serve as a parking lot manager.

-

Multi-thread Synchronization: Especially in scenarios where threads need to align activity in predefined ways. A semaphore can act as a signaling and synchronization mechanism.

-

Producer-Consumer: Often used in concurrent programming to facilitate communication between producer and consumer threads.

Here is the Python code:

import threading

# global variable x for modifying it

x = 0

def increment():

"""

function to increment global variable x

"""

global x

x += 1

def thread_task(mutex):

"""

task for thread

calls increment function 1000000 times.

"""

for _ in range(1000000):

mutex.acquire()

increment()

mutex.release()

def main_task():

global x

# setting global variable x as 0

x = 0

# creating a lock

mutex = threading.Lock()

# creating threads

t1 = threading.Thread(target=thread_task, args=(mutex,))

t2 = threading.Thread(target=thread_task, args=(mutex,))

# start threads

t1.start()

t2.start()

# wait until threads finish their job

t1.join()

t2.join()

if __name__ == "__main__":

for i in range(10):

main_task()

# after exiting the for loop, x should have become 2000000

print("iterations: {0}, x = {1}".format(i+1, x))In this code, a Lock object acts as a mutex to ensure mutual exclusion over the shared variable x.

Here is the output after running the code:

iterations: 1, x = 2000000

iterations: 2, x = 2000000

iterations: 3, x = 2000000

iterations: 4, x = 2000000

iterations: 5, x = 2000000

iterations: 6, x = 2000000

iterations: 7, x = 2000000

iterations: 8, x = 2000000

iterations: 9, x = 2000000

iterations: 10, x = 2000000

Explore all 40 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - Concurrency