You can also find all 80 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - Deep Learning

Deep Learning represents a subset of machine learning that emphasizes multi-layered artificial neural networks. These deep neural networks (DNNs) have the unparalleled ability to learn from unstructured or unlabeled data.

-

Neural Network Layers: Deep neural networks consist of multiple interconnected neural layers:

- Input Layer: Where data enters.

- Output Layer: Provides predictions or decisions.

-

Hidden Layers: Adapt data to enhance prediction accuracy (

$n \geq 1$ ).

-

Each Artificial Neuron in a Layer: Processes data using a weighted average, which is then transformed, usually nonlinearly. This output or activation is the input to neurons in the next layer.

-

Learning Process: Primarily achieved through gradient-based optimization, where the network minimizes a predefined loss or error function.

-

Feature Extraction: Instead of relying on pre-defined feature extraction, like traditional ML, Deep Learning models can learn representations directly from raw data.

-

Automated Feature Engineering: Deep Learning eliminates the need for manual feature engineering, allowing end-to-end learning.

-

Computer Vision: Deep Learning powers image and video analysis tasks, like object detection and image classification.

-

Speech Recognition: Virtual assistants and other speech recognition systems rely heavily on deep learning techniques.

-

Natural Language Processing: Tasks such as sentiment analysis, machine translation, and text classification benefit from the multi-layered structure of DNNs.

-

Automated Driving: Through the analysis of real-time data from various sensors in and around the vehicle, deep learning technologies play a crucial role in automated driving.

-

Drug Discovery and Genomics: Deep Learning is increasingly utilized for drug development and genomics studies to predict molecular activities, understand diseases, and facilitate therapy development.

An Artificial Neural Network (ANN) is an advanced computational model inspired by the human brain. It's characterized by its structure of interconnected nodes and their ability to perform tasks, such as pattern recognition, through learning algorithms.

-

Nodes (Neurons)

- Receives input signals, processes them, and generates an output signal.

- Applies an activation function to the combination of inputs and node weights to determine its output.

-

Edges (Synaptic Weights)

- Represent the strength of the connection between nodes.

- Adjusted during learning to optimize task performance.

-

Feedforward Neural Network (FNN)

- Information flows in one direction without loops.

- Commonly used in basic classification tasks.

-

Recurrent Neural Network (RNN)

- Internally possesses recurrent connections, enabling them to exhibit temporal dynamic behavior.

- Best suited for sequence-related tasks, such as natural language processing and speech recognition.

-

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Uses spatial arrangement of data in images to its advantage by applying a series of convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers.

- Specialized for tasks involving images, such as object detection and classification.

-

Modular Neural Network

- Comprises multiple, autonomous neural networks or neural-like circuits, each responsible for a specific sub-task.

-

Hybrid Neural Network

- Combines multiple neural network types to derive the benefits of each in solving particular kinds of problems.

- Supervised Learning: Labeled input data guides network learning.

- Unsupervised Learning: The network processes unlabeled data to find patterns and structures.

- Reinforcement Learning: Network learns via a feedback loop where it's rewarded or penalized based on its actions.

The functioning of an ANN is mathematically informed by methods such as the backpropagation algorithm and gradient descent, which iteratively optimizes network parameters to minimize error.

Activation functions, like the sigmoid or rectified linear unit (ReLU), produce nonlinear outputs critical for enabling ANNs to model complex relationships efficiently.

Nodes integrate weighted inputs, typically summing them up, then apply an activation function to the result. The weighted sum is often represented as:

Where:

-

$w_{i}$ and$x_{i}$ are the weights and inputs, respectively -

$b$ is the bias term -

$n$ is the number of inputs

In the context of Deep Learning, the term "depth" refers to the number of layers in a neural network, and is a key differentiator from traditional, shallow learning models.

The concept of depth in neural networks has a rich history, from some of the earliest explorations such as the Perceptron, to the challenges and breakthroughs that led to the resurgence of deep learning in the 21st century.

-

Early Research: When Frank Rosenblatt developed the Perceptron in 1958, the emphasis was on shallow, single-layer networks. These early networks had limitations in their ability to model complex, non-linear relationships. However, even at this early stage, researchers recognized the potential benefits of deeper architectures.

-

Vanishing Gradients: In the 1990s and early 2000s, it was established that training deep networks can be challenging due to vanishing or exploding gradients, attributed to certain activation functions and the accumulation of errors through backpropagation.

-

Resurgence with Improved Algorithms: The advent of techniques and architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, together with strategies for more efficient training, marked the re-emergence of deep learning.

Multiple theoretical and empirical studies have provided evidence for why the increased depth of neural networks adds to their expressive power and makes them computationally efficient.

-

Universal Function Approximators: Foundational work by Cybenko (1989) and Hornik (1991) demonstrated that shallow networks could approximate continuous functions on compact sets, but deeper networks could approximate these functions more efficiently.

-

The Curse of Dimensionality: In spaces of high dimensionality, simple models such as the perceptron or a shallow neural network may require an excessively large number of parameters to capture the required complexity. Deep networks achieve the same by learning a hierarchy of features in a more data-efficient manner.

-

Feature Abstractions: Deeper architectures sequentially encode input data into feature abstractions across layers. This process of hierarchical feature learning is instrumental in handling more complex tasks, such as object detection in images and automatic language translation.

-

Robustness to Local Minima: Deeper networks, with their multi-layer structures and abundant parameters, are less prone to getting stuck in undesirable local minima during optimization.

-

Information Flow and Gradient Signal: A deeper neural network can propagate the initial input (or its influence) more directly to the output layer. This enhanced information flow promotes better gradient signal back through the layers during training.

-

Ensemble Effects: Deeper architectures take on an inherent ensemble-like quality as they learn feature hierarchies. This enables them to encapsulate more data nuances, making them less sensitive to small perturbations.

While depth offers several advantages, it can also introduce challenges, particularly related to computational resources and training complexity.

-

Computational Demand: Deeper networks often require increased computational resources for both training and inference. This necessity can present a practical limitation in resource-constrained environments.

-

Vanishing and Exploding Gradients: Despite various techniques to mitigate these issues (e.g., careful weight initialization, batch normalization), deep networks can still be susceptible to gradient problems during training.

-

Overfitting: There is a non-negligible risk of overfitting when training deep networks, especially if the training dataset is limited or noisy.

-

Training Time and Data Requirements: Deeper models typically need more extensive training sessions and larger datasets to be effectively generalized.

-

Model Interpretability: As models grow in depth, their interpretability often diminishes. Understanding how each feature or layer contributes to the final prediction can become a daunting task.

Several theoretical perspectives have been employed to analyze and understand the reasons behind the success of deep models.

-

VC Dimension: With a focus on pattern recognition and classification tasks, the Vapnik-Chervonenkis (VC) dimension captures the number of training patterns a model's learning algorithm can adopt.

-

Information Bottleneck Theory: This framework emphasizes the necessity to balance the amount of information a layer retains about its input and its target output.

-

Minimum Description Length (MDL): Informed by algorithmic information theory, this approach seeks to minimize the coding length of the representation.

-

Biological Plausibility: Insights from neuroscience and the functioning of animal brains have inspired the development of deep learning architectures to mirror certain observed principles from biological systems.

The decision to increase the depth of a neural network is not to be taken lightly. It involves trade-offs and considerations such as computational cost, available data, and the task's complexity. While depth can imbue networks with powerful representational abilities, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

The rich historic context, modern empirical evidence, and theoretical underpinnings together paint a comprehensive picture of why depth in neural networks is both a fascinating subject of study and a critical factor in their practical success.

Activation functions play a crucial role in deep learning by introducing non-linearity to the model. This enables the neural network to learn complex patterns and achieve accurate predictions.

-

Without non-linearity, the entire neural network reduces to a single-layer model, making it incapable of learning from intricate, real-world data.

-

To understand why, consider a network that only performs linear transformations (

$y = mx + b$ ). No matter the number of layers, the output will be a linear combination of the inputs, simplifying the entire network to a single linear transformation.

-

Introducing Non-linearity: Without this property, neural networks would be limited to linear transformations, processing data in a simplistic manner that fails to capture complex relationships.

-

Signal Regulation: Activation functions, acting on the weighted sum of inputs from the previous layer, determine if and to what extent this information is passed on to the next layer.

-

Statistical Efficiency: Through various compression techniques, activation functions help reduce the dimensionality and scale the numerical value of signals, speeding up training and network convergence.

- Binary Step: Useful in systems where an outcome can only have two states, e.g., binary classifiers.

-

Linear: While the properties of non-linearity are lacking, linear activations are useful in specialized models such as linear regressions.

-

Sigmoid (Logistic): S-shaped curve, suitable for producing a probability value, i.e., in binary classifiers.

- Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU): Widely used, it activates for positive inputs, setting negative inputs to zero. Its simple computational structure and avoidance of the vanishing gradient problem have made it a favorite.

- Leaky ReLU: An enhanced version of ReLU that addresses its limitation for negative inputs. Instead of setting negatives to zero, it multiplies them by a small constant, typically 0.01.

- Hyperbolic Tangent (Tanh): Scaled version of the sigmoid, its range lies between -1 and 1. This makes it useful for tasks where inputs are normalized.

- Softmax: Suitable for multi-class classification, it squashes a K-dimensional vector of arbitrary values to K-dimensional, non-negative, and sums-to-one values, resembling probabilities.

The neural network utilizes both weights and biases to transform input data into the corresponding output.

- Definition: Weights are multiplicative parameters, learned during training, that assign different importances to input features before they are passed through the activation functions of the network.

- Responsibility: They discern the significance of individual inputs for making predictions.

- Updating Strategy: Often initialized randomly, weights are adjusted via backpropagation and an optimization algorithm such as gradient descent to minimize the network's training error or loss function.

- Impact: The magnitude of the updates directly relates to the partial derivative of the loss function with respect to the weights, which in turn affects the direction and rate at which the model learns from the data.

- Definition: Biases are additive parameters, also learned during training, that help the network better model the relationships between features and the target by offsetting the output of the weighted sum before it passes through the activation functions.

- Responsibility: Bias terms can enable the model to make accurate predictions even when all input features are zero. They also play a crucial role in enabling the network to fit data with complex relationships.

- Updating Strategy: Initialized as zeros (though this may vary), biases are also updated through backpropagation to minimize the network's error or loss.

- Impact: They influence the direction and rate of learning in a similar manner as weights; however, biases do not modify the inputs themselves but rather add a constant term to the neuron's activation.

The Vanishing Gradient Problem arises in deep neural networks when gradients become increasingly small as they propagate backward through multiple layers during training.

- In neural networks with deep architectures, the chain rule multiplies many gradients during backpropagation. If these gradients are smaller than 1, their product diminishes as it's repeatedly multiplied, leading to vanishing gradients.

- Activation functions also play a role. The sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent functions, for example, have derivatives which snugly fit within the 0 to 1 range.

-

Weight Initialization:

- Starting with appropriate initial weights can reduce the likelihood of vanishing gradients.

- For sigmoid and hyperbolic tangent activations, weights are typically initialized with a smaller range like

$[-0.1, 0.1]$ .

-

Batch Normalization:

- This technique standardizes the input of each layer. This can reduce internal covariate shift, which can act as a form of regularization and also speed up training.

-

LSTM and GRU Cells:

- These recurrent neural network (RNN) units are explicitly designed to tackle long-term dependencies by incorporating gating mechanisms. This helps in controlling information flow during both forward and backward passes.

-

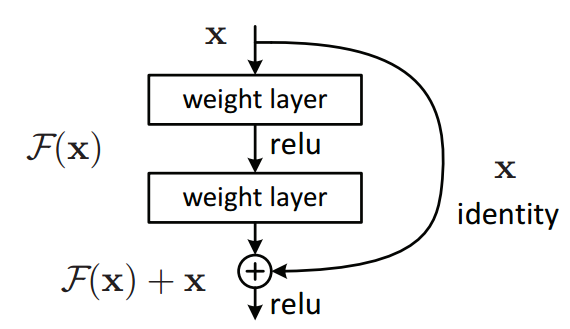

Residual Connections (ResNets):

- These are a type of architecture, generally for convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which allow for direct connections between layers. This helps stabilize the training process and can mitigate vanishing gradients.

-

Gradient Clipping:

- Setting a threshold for the norm of the gradient can prevent it from becoming too small or too large. Processes like LSTM-based text generation can benefit from this.

-

Avoiding Vanishing Exploding Gradients with RNNs:

- Sequences in RNNs are often of variable length. During backpropagation through time (BPTT), these sequences can be quite long, leading to potential gradient explosion or vanishing. Techniques like truncated BPTT can effectively address this.

-

Weight Initialization Strategies:

- Techniques like Xavier and He initialization ensure more stable initial weights.

-

Layer-Specific Learning Rates:

- Adaptive methods like ADAM adjust learning rates dynamically, potentially benefiting layers with vanishing gradients.

-

Hierarchical Memory Units:

- Techniques like the Neural Turing Machine (NTM) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks utilize specialized, context-preserving memory cells.

Shallow neural networks have a limited number of layers while deep neural networks (> 3) layers are characterized by a deeper, more complex architecture.

-

Feature Transformation: Shallow networks perform linear transformations, while deep networks extract hierarchical features through non-linear activation functions in multiple layers.

-

Representation Learning: Deep networks, because of their multilayer structure, have the capacity to learn, represent, and disentangle intricate data features.

-

Generalization: Deep networks, by integrating both shallow and deep features, are generally better at generalizing on unseen data.

-

Feature Abstraction: Deep networks excel at learning abstract and high-level representations, whereas shallow networks often remain at the level of input features.

-

Modeling Complex Relationships: Deep networks are adept at capturing complex, non-linear relationships in data, making them well-suited for tasks that shallow networks would struggle with, such as image and speech recognition.

Here is the Python code:

import tensorflow as tf

# Define a shallow neural network with 1 hidden layer

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Dense(10, activation='relu', input_shape=(100,)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')

])Here is the Python code:

import tensorflow as tf

# Define a deep neural network with 3 hidden layers

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Dense(100, activation='relu', input_shape=(100,)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(50, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(25, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')

])The Universal Approximation Theorem (UAT) establishes the remarkable capability of certain types of neural networks to approximate essentially any continuous function.

This theorem laid the foundation for the widespread adoption of neural networks and remains an essential theoretical underpinning to deep learning.

The UAT demonstrates that under certain conditions, functions of the form:

where

Two key theorems underpin the UAT:

-

Cybenko's Theorem (1989): A feedforward neural network with a single hidden layer and a finite number of neurons can approximate any continuous function on a compact input domain to arbitrary precision.

-

Hornik's Theorem (1991): A feedforward neural network with a single layer can approximate any Borel measurable function to arbitrary precision. If the activation function is also bounded and continuous, then the result is extended to continuous functions.

The UAT gives both a justified reasoning and a boundary condition for why neural networks, particularly those with a single hidden layer, can be highly effective in many practical scenarios.

While the UAT has been instrumental in the rise of neural networks, it's worth noting that the theorem does not prescribe practical network configurations, such as the number of neurons needed.

In practical ML applications, while networks with only a single hidden layer suffice in theory, they may not always be the most effective in practice. Deep neural networks, with multiple layers, are often utilized for their superior learning and generalization abilities.

Deep learning offers substantial benefits over shallow architectures in numerous tasks. Although the UAT is an indispensable theoretical landmark, its focus on shallow architectures might offer a less comprehensive view of the learning and expressive capabilities of deep neural networks.

Given the rapid advancements in the field, especially pertaining to overfitting, convergence, and extensions of optimization algorithms to deep networks, an ongoing discussion on the practical implications and limitations of these theorems is warranted.

Indeed, while the UAT detailing the approximation capability has proven to be invaluable, newer theories and experiments demonstrate that depth can offer distinct learning advantages, establishing the need for a more nuanced understanding of the learning dynamics in increasingly large-scale deep models.

Dropout layers in neural networks are a powerful weapon against overfitting.

The dropout mechanism involves randomly "turning off" a fraction of the neurons (along with their respective weights and biases) in each training step. This prevents co-adaptation of neurons, a process where individual neurons rely excessively on specific contexts provided by other neurons.

During training, each neuron has a probability

During the evaluation (or inference) phase, all neurons are retained, but their outputs are scaled down by a factor of

# Example: Dropout layer in TensorFlow

import tensorflow as tf

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Dense(64, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.5) # 50% dropout

])

# Each neuron 'drop-out' probability in the second layer is 0.5

training_output = model(features, training=True)

# The model is running in evaluation mode without dropout

evaluation_output = model(features, training=False)Akin to L1 and L2 regularizations, dropout infuses randomness, reducing the model's dependency on specific neurons and therefore making the learning process more robust.

One way to conceptualize dropout's effect is that each training iteration explores a different combination of neurons, effectively training multiple smaller sub-networks. The final model can then be viewed as an ensemble of these sub-networks, which often yields better predictive performance.

Forward propagation involves the initial flow of input data through the layers of a neural network, whereas backpropagation is the subsequent flow of error signals from the network's output back to its input, updating the model's weights to minimize the error.

- Initialize Weights: Randomly set the neural network's weights.

- Linear Transformation and Activation: For each layer, multiply the inputs by the layer's weights and apply an activation function.

- Calculate Loss: Use a loss function to measure the discrepancy between the model's predictions and the actual outputs.

- Aggregating Predictions: Summarize the model's predictions, often using a "sum" or "last layer output" approach.

- Compute Gradients: Calculate the gradients of the loss function with respect to each weight in the network.

- Update Weights: Use the computed gradients to update the weights, typically employing a learning rate to control the update step's size.

- Iterate: Repeat the above steps until the model's performance (measured by the loss function) is satisfactory, and an optimal set of weights is found.

The model makes a prediction

The loss, denoted by

The chain rule is applied to get the gradients for the weights in each layer.

Here is the Python code:

import numpy as np

# Input features

X = np.array([[0, 0], [0, 1], [1, 0], [1, 1]])

# True output

Y = np.array([[0], [1], [1], [0]])

# Sigmoid activation function

def sigmoid(x):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-x))

# Derivative of sigmoid

def sigmoid_derivative(x):

return x * (1 - x)

# Initialize the weights

hidden_weights = np.random.rand(2, 2)

output_weights = np.random.rand(2, 1)

# Forward Pass

def forward_pass(inputs, weights1, weights2):

hidden_input = np.dot(inputs, weights1)

hidden_output = sigmoid(hidden_input)

output = sigmoid(np.dot(hidden_output, weights2))

return hidden_input, hidden_output, output

# Backward Pass

def backward_pass(inputs, hidden_output, output, hidden_input, true_labels,

learning_rate, weights1, weights2):

output_error = true_labels - output

output_gradient = sigmoid_derivative(output)

hidden_error = np.dot(output_error * output_gradient, weights2.T)

hidden_gradient = sigmoid_derivative(hidden_input)

weights2 += np.dot(hidden_output.T, (output_error * output_gradient)) * learning_rate

weights1 += np.dot(inputs.T, (hidden_error * hidden_gradient)) * learning_rate

return weights1, weights2A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning model tailored for tasks involving visual data, such as image or video recognition.

Its unique architecture takes into account the spatial nature of images, handling them more efficiently than traditional deep learning models like standard multilayer perceptrons.

-

Convolutional Layer: This layer uses sliding filter windows to perform convolutions, extracting features in a localized manner. These filters range from simple edge detectors to more complex shapes. Activation maps visualize the features extracted by these filters.

-

Pooling Layer: By reducing image dimensions, pooling layers enhance computational efficiency and minimize overfitting. Common practices include max-pooling (selecting the maximum value from a local cluster) and average-pooling (using the mean).

-

Flattening Layer: This layer converts the 2D feature maps from the preceding layers into a 1D array, preparing the data for entrance into a traditional feed-forward neural network, or densely connected layer.

-

Densely Connected Layer: This layer utilizes the entire feature space from the preceding layers to fine-tune the learned features and make predictions.

CNNs are ideal for visual data-processing tasks due to their specialized architecture for image analysis:

- Image Classification: Assigning labels to entire images.

- Object Detection and Localisation: Identifying objects within an image and marking their location.

- Image Segmentation: Dividing an image into distinct regions, such as using pixel masks to semantically segment objects.

- Face Recognition: Identifying and verifying human faces in photos or videos.

- Action Recognition: Recognizing and classifying human actions from video data.

- Artistic Style Transfer: Rendering images in different artistic styles, such as Van Gogh's "Starry Night."

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a class of deep learning models specifically designed to handle sequential data. They achieve this capability through internal memory, enabling them to process inputs of varying lengths while considering temporal dependencies.

-

Recurrent Layer: This layer, represented by an arrow looping back on itself, gives RNNs their memory. At each time step, it produces an output and updates its internal state, which is then used at the next time step.

-

Time Steps: Input sequences, such as sentences or time-series data, are broken down into time steps. RNNs process these steps one after the other, with each step updating the network's internal state.

-

Output Sequence: RNNs can produce both an internal state after each time step and, potentially, an output. Additionally, they can generate an output for each time step, or just at the end of the sequence.

-

Natural Language Processing (NLP): RNNs are fundamental to language tasks like sentiment analysis, named entity recognition, and machine translation.

-

Time Series Analysis: They're effective for tasks such as stock price prediction, weather forecasting, and anomaly detection.

-

Speech Recognition and Generation: RNNs enable systems to transcribe human speech into text and, conversely, generate human-like speech.

-

Music Generation: RNNs can learn the temporal structure of music and compose new melodies.

-

Video Analysis: Applications range from action recognition in videos to video summarization.

-

Medical Applications: RNNs help in tasks like heart rate classification, electrocardiogram (ECG) analysis, and patient monitoring.

-

Recommender Systems: For providing personalized recommendations by analyzing user-item interaction sequences.

-

Robotics and Control: For time-dependent tasks, like robot motion planning and control.

-

Computational Biology: They're used for tasks involving sequential biological data such as protein structure prediction and gene regulatory network modeling.

-

Spatiotemporal Data: For understanding data that has both spatial and temporal elements, such as in meteorological and geographical analyses.

-

Online Gaming: In AI opponents for adapting strategies, tracking user behavior, and more.

Here is a Python code:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

# Define RNN model

class RNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, hidden_size, output_size):

super(RNN, self).__init()

self.hidden_size = hidden_size

self.rnn = nn.RNN(input_size, hidden_size, batch_first=True)

self.fc = nn.Linear(hidden_size, output_size)

def forward(self, x):

h0 = torch.zeros(1, x.size(0), self.hidden_size)

out, _ = self.rnn(x, h0)

out = self.fc(out[:, -1, :])

return out

# Instantiate the model

rnn = RNN(input_size=100, hidden_size=50, output_size=10)

# Define Loss and Optimizer

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(rnn.parameters(), lr=0.01)

# Train the model

for inputs, labels in train_loader:

outputs = rnn(inputs)

loss = criterion(outputs, labels)

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()LSTMs are a type of RNN with a more sophisticated structure that helps mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, making them particularly effective for tasks handling sequential data.

- Gates: LSTMs have three gates to protect and control the cell state:

- input gate: what to keep and add to the memory cell

- forget gate: what to remove from the memory cell

- output gate: what to output based on the cell state

These gates can be thought of as "regulators" of the information flow through the cell state, using sigmoid neural nets to control the flow of information.

The equation for the input (sigmoid) and forget gate (sigmoid) are:

-

Candidate Values: This is the addition to the state that is computed, but not used yet. The candidate value is computed similarly to the cell state, but using a

$\tanh$ activation function.

$$ \tilde{C}t = \tanh(W_C \cdot [h{t-1}, x_t] + b_C) $$

Then, the state is updated:

- Output State: This output completely depends on the cell state, but is a filtered version. The output is found by running a sigmoid activation function on the cell state, and then the new cell state is computed.

-

Language Modeling: Predicting the next word in a sentence.

-

Machine Translation: Such as translating English to French or any other language.

-

Image Captioning: Generating descriptions of images.

-

Speech Recognition: Converting speech to text.

-

Text Summarization: Generating a shorter text from a longer text.

-

Generating Music: Composing pieces of music.

Residual Networks, or ResNets, are a meaningful architectural development that have significantly impacted the field of deep learning by alleviating the vanishing gradient problem. This divergence from traditional architectures has enabled substantially deeper neural networks, leading to improved accuracy in both training and testing stages.

In conventional feedforward neural networks, as the gradients back-propagate from the output layer to the input layer during training, they can become exceedingly small. This effect, known as the vanishing gradient problem, leads to sluggish learning, especially in deep networks.

Mathematically, the vanishing gradient problem can be represented as:

where

ResNets address the vanishing gradient problem using shortcut connections, also referred to as skip connections. These unique features allow for direct information flow between layers, mitigating the issue of vanishing gradients and thereby improving training of very deep networks.

The skip connection can be defined as:

Mathematically, this helps to prevent the vanishing gradient problem, ensuring that

The structure of a ResNet block is often illustrated as follows:

ResNets, with their characteristic deep layering, have produced state-of-the-art performance on several benchmark image classification tasks. These tasks include the well-known ImageNet dataset.

The consistent top rankings in these competitions have secured ResNets as a vital component of modern deep learning toolkits.

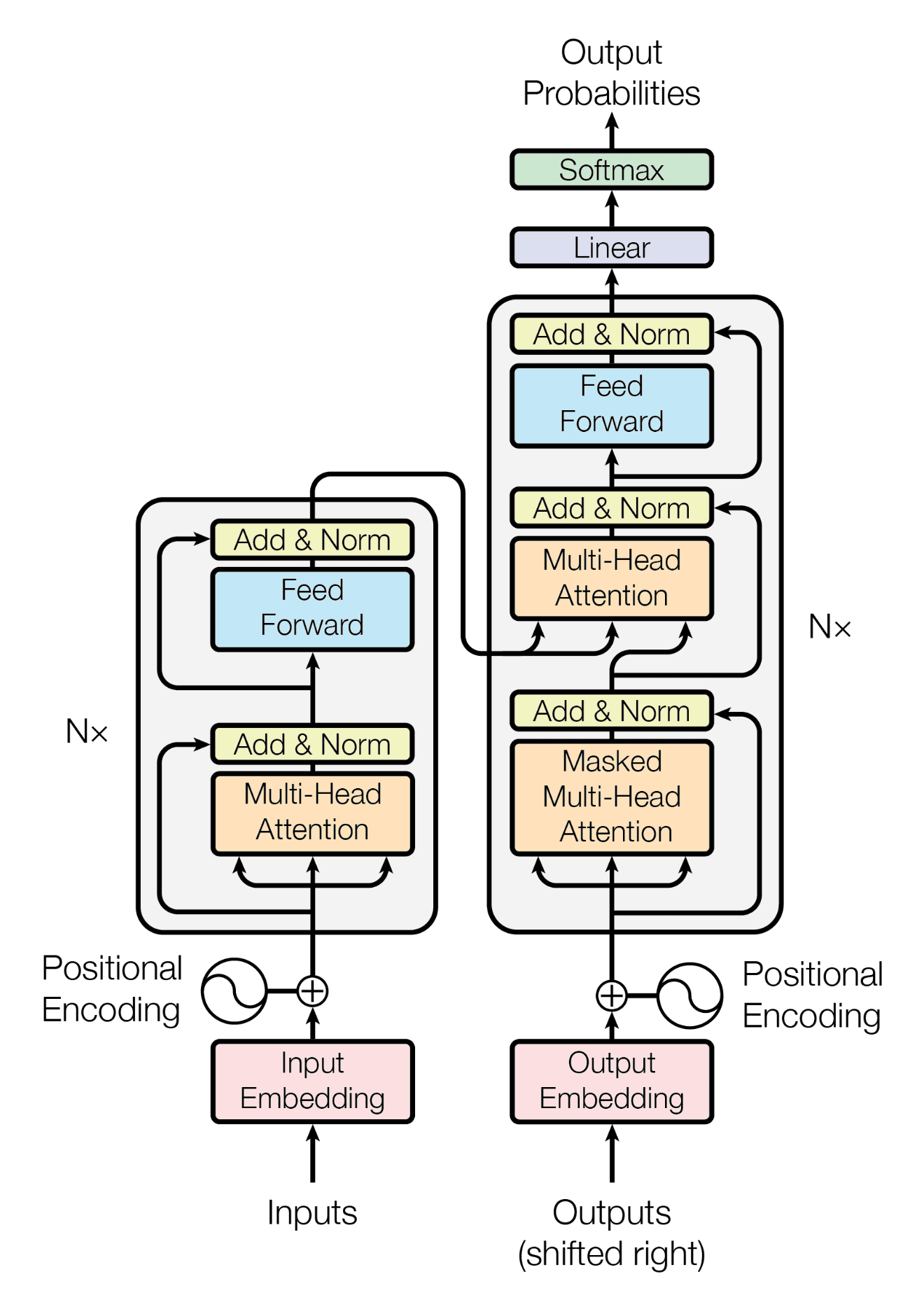

The Transformer architecture is a type of neural network that has made a considerable impact in natural language processing (NLP) tasks, thanks to its parallel processing and scalability. It eliminates the need for recurrent or convolutional layers, which can be computationally expensive.

-

Encoder: The input sequence is represented through a set of hidden states that capture its contextual information. Each input token initially undergoes embedding, where its unique index is converted into a continuous vector, and the positional encoding ensures the network understands token order.

-

Self-Attention Mechanism: Multi-headed attention helps the network focus on different parts of the input, seeking out relevant tokens. The indications provided by the attention mechanism directly influence the network's decisions, thereby addressing the vanishing gradient problem.

-

Position-Wise Feed-Forward Networks: Hidden representations from each position are independently processed using these brief, two-layer networks.

-

Decoder: The decoder component in a sequence-to-sequence neural network model processes the output sequence.

- Parallel Computations: Transformers afford greater computational speed by allowing simultaneous processing of input tokens.

- Bidirectional Information: Unlike RNNs, which process input sequentially, Transformers can gather both past and future context, enhancing their understanding of the sequence.

- Stable Gradients: The use of self-attention and layer normalization ensures that gradients are propagated more reliably.

- Reduced Training Time: The absence of recurrent connections optimizes the training process.

- Token Limitation: Transformers are constrained by the number of tokens they can process at once.

- Inability to Handle Sequential Data: As they disregard token order, their use in sequential data is limited.

- High Memory Expenditure: While training, they amass substantial memory due to the need to preserve attention weights.

Although they are best known for NLP applications, transformers have found utility in diverse domains like:

- Image Generation and Recognition: Use of the Vision Transformer (ViT) model.

- Drug Design and Bioinformatics: Identifying molecular structures or generating new ones.

- Recommender Systems: Better learn complex user-item interactions.

Some applications might bypass text input altogether and still take advantage of the transformers' strengths in data processing.

Explore all 80 answers here 👉 Devinterview.io - Deep Learning