| tags | title | |

|---|---|---|

|

Builder |

tags: #cleancode/designpatterns

Builder is a creational design pattern that lets you construct complex objects step by step. The pattern allows you to produce different types and representations of an object using the same construction code.

Imagine a complex object that requires laborious, step-by-step initialization of many fields and nested objects. Such initialization code is usually buried inside a monstrous constructor with lots of parameters. Or even worse: scattered all over the client code.

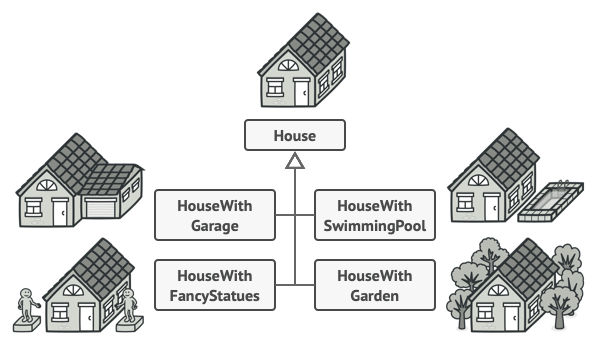

You might make the program too complex by creating a subclass for every possible configuration of an object.

For example, let’s think about how to create a House object. To build a simple house, you need to construct four walls and a floor, install a door, fit a pair of windows, and build a roof. But what if you want a bigger, brighter house, with a backyard and other goodies (like a heating system, plumbing, and electrical wiring)?

The simplest solution is to extend the base House class and create a set of subclasses to cover all combinations of the parameters. But eventually you’ll end up with a considerable number of subclasses. Any new parameter, such as the porch style, will require growing this hierarchy even more.

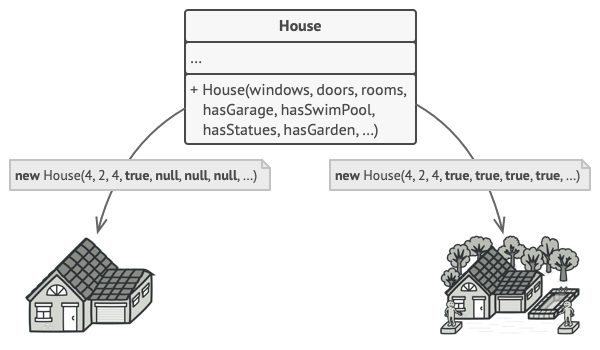

There’s another approach that doesn’t involve breeding subclasses. You can create a giant constructor right in the base House class with all possible parameters that control the house object. While this approach indeed eliminates the need for subclasses, it creates another problem.

The constructor with lots of parameters has its downside: not all the parameters are needed at all times.

In most cases most of the parameters will be unused, making the constructor calls pretty ugly. For instance, only a fraction of houses have swimming pools, so the parameters related to swimming pools will be useless nine times out of ten.

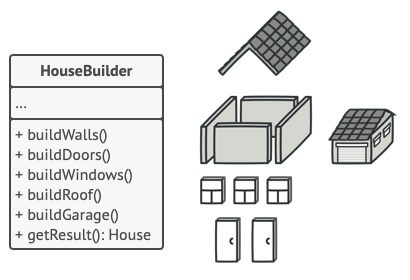

The Builder pattern suggests that you extract the object construction code out of its own class and move it to separate objects called builders.

The Builder pattern lets you construct complex objects step by step. The Builder doesn’t allow other objects to access the product while it’s being built.

The pattern organizes object construction into a set of steps (buildWalls, buildDoor, etc.). To create an object, you execute a series of these steps on a builder object. The important part is that you don’t need to call all of the steps. You can call only those steps that are necessary for producing a particular configuration of an object.

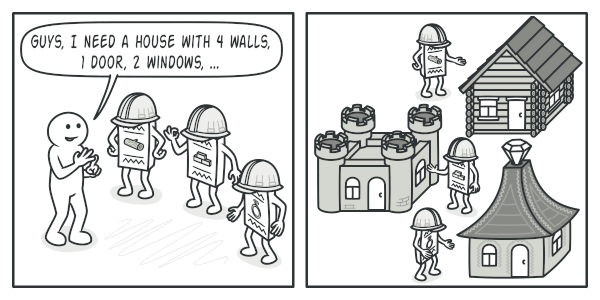

Some of the construction steps might require different implementation when you need to build various representations of the product. For example, walls of a cabin may be built of wood, but the castle walls must be built with stone.

In this case, you can create several different builder classes that implement the same set of building steps, but in a different manner. Then you can use these builders in the construction process (i.e., an ordered set of calls to the building steps) to produce different kinds of objects.

Different builders execute the same task in various ways.

For example, imagine a builder that builds everything from wood and glass, a second one that builds everything with stone and iron and a third one that uses gold and diamonds. By calling the same set of steps, you get a regular house from the first builder, a small castle from the second and a palace from the third. However, this would only work if the client code that calls the building steps is able to interact with builders using a common interface.

You can go further and extract a series of calls to the builder steps you use to construct a product into a separate class called director. The director class defines the order in which to execute the building steps, while the builder provides the implementation for those steps.

The director knows which building steps to execute to get a working product.

Having a director class in your program isn’t strictly necessary. You can always call the building steps in a specific order directly from the client code. However, the director class might be a good place to put various construction routines so you can reuse them across your program.

In addition, the director class completely hides the details of product construction from the client code. The client only needs to associate a builder with a director, launch the construction with the director, and get the result from the builder.

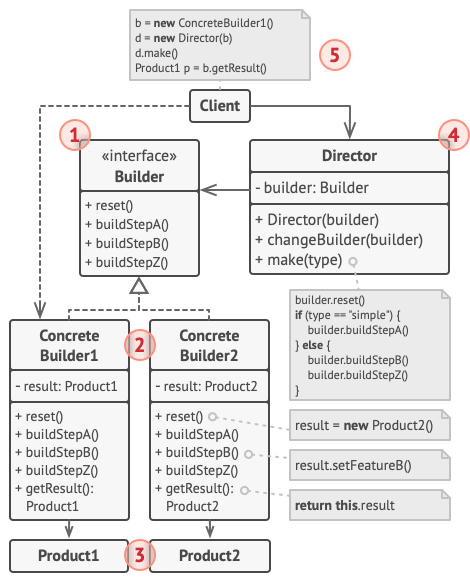

- The Builder interface declares product construction steps that are common to all types of builders.

- Concrete Builders provide different implementations of the construction steps. Concrete builders may produce products that don’t follow the common interface.

- Products are resulting objects. Products constructed by different builders don’t have to belong to the same class hierarchy or interface.

- The Director class defines the order in which to call construction steps, so you can create and reuse specific configurations of products.

- The Client must associate one of the builder objects with the director. Usually, it’s done just once, via parameters of the director’s constructor. Then the director uses that builder object for all further construction. However, there’s an alternative approach for when the client passes the builder object to the production method of the director. In this case, you can use a different builder each time you produce something with the director.

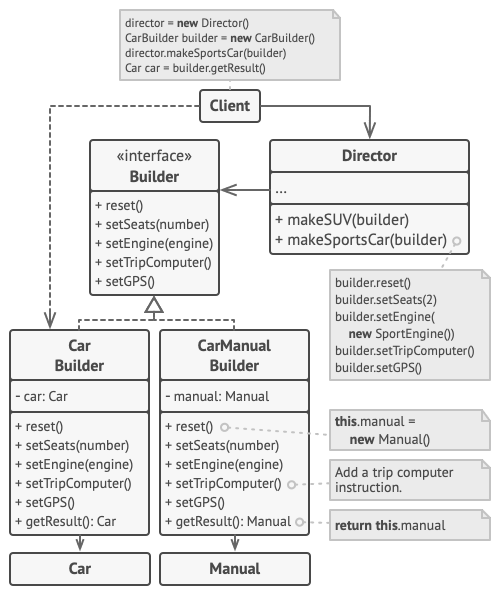

This example of the Builder pattern illustrates how you can reuse the same object construction code when building different types of products, such as cars, and create the corresponding manuals for them.

The example of step-by-step construction of cars and the user guides that fit those car models.

A car is a complex object that can be constructed in a hundred different ways. Instead of bloating the Car class with a huge constructor, we extracted the car assembly code into a separate car builder class. This class has a set of methods for configuring various parts of a car.

If the client code needs to assemble a special, fine-tuned model of a car, it can work with the builder directly. On the other hand, the client can delegate the assembly to the director class, which knows how to use a builder to construct several of the most popular models of cars.

You might be shocked, but every car needs a manual (seriously, who reads them?). The manual describes every feature of the car, so the details in the manuals vary across the different models. That’s why it makes sense to reuse an existing construction process for both real cars and their respective manuals. Of course, building a manual isn’t the same as building a car, and that’s why we must provide another builder class that specializes in composing manuals. This class implements the same building methods as its car-building sibling, but instead of crafting car parts, it describes them. By passing these builders to the same director object, we can construct either a car or a manual.

The final part is fetching the resulting object. A metal car and a paper manual, although related, are still very different things. We can’t place a method for fetching results in the director without coupling the director to concrete product classes. Hence, we obtain the result of the construction from the builder which performed the job.

// Using the Builder pattern makes sense only when your products

// are quite complex and require extensive configuration. The

// following two products are related, although they don't have

// a common interface.

class Car is

// A car can have a GPS, trip computer and some number of

// seats. Different models of cars (sports car, SUV,

// cabriolet) might have different features installed or

// enabled.

class Manual is

// Each car should have a user manual that corresponds to

// the car's configuration and describes all its features.

// The builder interface specifies methods for creating the

// different parts of the product objects.

interface Builder is

method reset()

method setSeats(...)

method setEngine(...)

method setTripComputer(...)

method setGPS(...)

// The concrete builder classes follow the builder interface and

// provide specific implementations of the building steps. Your

// program may have several variations of builders, each

// implemented differently.

class CarBuilder implements Builder is

private field car:Car

// A fresh builder instance should contain a blank product

// object which it uses in further assembly.

constructor CarBuilder() is

this.reset()

// The reset method clears the object being built.

method reset() is

this.car = new Car()

// All production steps work with the same product instance.

method setSeats(...) is

// Set the number of seats in the car.

method setEngine(...) is

// Install a given engine.

method setTripComputer(...) is

// Install a trip computer.

method setGPS(...) is

// Install a global positioning system.

// Concrete builders are supposed to provide their own

// methods for retrieving results. That's because various

// types of builders may create entirely different products

// that don't all follow the same interface. Therefore such

// methods can't be declared in the builder interface (at

// least not in a statically-typed programming language).

//

// Usually, after returning the end result to the client, a

// builder instance is expected to be ready to start

// producing another product. That's why it's a usual

// practice to call the reset method at the end of the

// `getProduct` method body. However, this behavior isn't

// mandatory, and you can make your builder wait for an

// explicit reset call from the client code before disposing

// of the previous result.

method getProduct():Car is

product = this.car

this.reset()

return product

// Unlike other creational patterns, builder lets you construct

// products that don't follow the common interface.

class CarManualBuilder implements Builder is

private field manual:Manual

constructor CarManualBuilder() is

this.reset()

method reset() is

this.manual = new Manual()

method setSeats(...) is

// Document car seat features.

method setEngine(...) is

// Add engine instructions.

method setTripComputer(...) is

// Add trip computer instructions.

method setGPS(...) is

// Add GPS instructions.

method getProduct():Manual is

// Return the manual and reset the builder.

// The director is only responsible for executing the building

// steps in a particular sequence. It's helpful when producing

// products according to a specific order or configuration.

// Strictly speaking, the director class is optional, since the

// client can control builders directly.

class Director is

private field builder:Builder

// The director works with any builder instance that the

// client code passes to it. This way, the client code may

// alter the final type of the newly assembled product.

method setBuilder(builder:Builder)

this.builder = builder

// The director can construct several product variations

// using the same building steps.

method constructSportsCar(builder: Builder) is

builder.reset()

builder.setSeats(2)

builder.setEngine(new SportEngine())

builder.setTripComputer(true)

builder.setGPS(true)

method constructSUV(builder: Builder) is

// ...

// The client code creates a builder object, passes it to the

// director and then initiates the construction process. The end

// result is retrieved from the builder object.

class Application is

method makeCar() is

director = new Director()

CarBuilder builder = new CarBuilder()

director.constructSportsCar(builder)

Car car = builder.getProduct()

CarManualBuilder builder = new CarManualBuilder()

director.constructSportsCar(builder)

// The final product is often retrieved from a builder

// object since the director isn't aware of and not

// dependent on concrete builders and products.

Manual manual = builder.getProduct()-

Use the Builder pattern to get rid of a “telescoping constructor”. Say you have a constructor with ten optional parameters. Calling such a beast is very inconvenient; therefore, you overload the constructor and create several shorter versions with fewer parameters. These constructors still refer to the main one, passing some default values into any omitted parameters.

class Pizza { Pizza(int size) { ... } Pizza(int size, boolean cheese) { ... } Pizza(int size, boolean cheese, boolean pepperoni) { ... } // ...

Creating such a monster is only possible in languages that support method overloading, such as C# or Java.

The Builder pattern lets you build objects step by step, using only those steps that you really need. After implementing the pattern, you don’t have to cram dozens of parameters into your constructors anymore.

-

Use the Builder pattern when you want your code to be able to create different representations of some product (for example, stone and wooden houses). The Builder pattern can be applied when construction of various representations of the product involves similar steps that differ only in the details.

The base builder interface defines all possible construction steps, and concrete builders implement these steps to construct particular representations of the product. Meanwhile, the director class guides the order of construction.

-

Use the Builder to construct Composite trees or other complex objects. The Builder pattern lets you construct products step-by-step. You could defer execution of some steps without breaking the final product. You can even call steps recursively, which comes in handy when you need to build an object tree.

A builder doesn’t expose the unfinished product while running construction steps. This prevents the client code from fetching an incomplete result.

-

Make sure that you can clearly define the common construction steps for building all available product representations. Otherwise, you won’t be able to proceed with implementing the pattern.

-

Declare these steps in the base builder interface.

-

Create a concrete builder class for each of the product representations and implement their construction steps.

Don’t forget about implementing a method for fetching the result of the construction. The reason why this method can’t be declared inside the builder interface is that various builders may construct products that don’t have a common interface. Therefore, you don’t know what would be the return type for such a method. However, if you’re dealing with products from a single hierarchy, the fetching method can be safely added to the base interface.

-

Think about creating a director class. It may encapsulate various ways to construct a product using the same builder object.

-

The client code creates both the builder and the director objects. Before construction starts, the client must pass a builder object to the director. Usually, the client does this only once, via parameters of the director’s class constructor. The director uses the builder object in all further construction. There’s an alternative approach, where the builder is passed to a specific product construction method of the director.

-

The construction result can be obtained directly from the director only if all products follow the same interface. Otherwise, the client should fetch the result from the builder.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| You can construct objects step-by-step, defer construction steps or run steps recursively. | The overall complexity of the code increases since the pattern requires creating multiple new classes. |

| You can reuse the same construction code when building various representations of products. | |

| [[CleanCode/Single Responsibility Principle]]. You can isolate complex construction code from the business logic of the product. |

- Many designs start by using [[CleanCode/Factory]] Method (less complicated and more customizable via subclasses) and evolve toward [[CleanCode/Abstract Factory]], [[CleanCode/Prototype]], or [[CleanCode/Builder]] (more flexible, but more complicated).

- Builder focuses on constructing complex objects step by step. [[CleanCode/Abstract Factory]] specializes in creating families of related objects. [[CleanCode/Abstract Factory]] returns the product immediately, whereas Builder lets you run some additional construction steps before fetching the product.

- You can use Builder when creating complex [[CleanCode/Composite]] trees because you can program its construction steps to work recursively.

- You can combine Builder with [[CleanCode/Bridge]]: the director class plays the role of the abstraction, while different builders act as implementations.

- [[CleanCode/Abstract Factory|Abstract Factories]], [[CleanCode/Builder|Builders]] and [[CleanCode/Prototype|Prototypes]] can all be implemented as [[CleanCode/Singleton|Singletons]].