This section includes a map of different learning dimensions which are possible and likely to emerge from taking part in this game making course.

It is inspired by the work of Bevan and Petrich around their study of 'tinkering' in science museums, who through close observation in partnership with learning facilitators mapped some of the complex learning processes which may be hard to spot in a quite chaotic and messy learning environment.

Other ideas behind the structure of this section are explored here.

These concepts are needed to put Algorithmic Thinking into practice. The following are loosely based on the computational thinking concepts of Brennan and Resnick.

-

Description: Tasks that can be expressed as a series of steps.

-

Why is it needed : Computers don't have common sense. They need precise instructions that are broken down into individual steps. The order that tasks happen in is significant. Some bugs are due to errors to commands being run in the wrong sequence.

-

How it happens in practice: You would put the sequence inside a on start block. An example from our starting template is below.

A common practice when there is a set of instructions that might be run in more than one situation, or to keep code neat is to create a separate function. The last block of the code above does that.

- Examples in our Game Patterns: Add Player Lives,

-

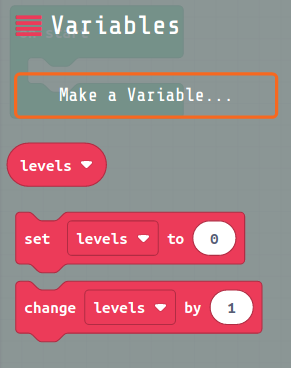

Description: Variables are a kind of data that allow storing, retrieving, and updating values.

-

Why is it needed : Variables are useful when we know something may change when our program is running. For example if we create more than one level, we can create a variable called level and increase this each time a player progresses.

-

How it happens in practice: You can create and set variable us using blocks in the Variable section.

- Examples in our Game Patterns: Add More Levels,

-

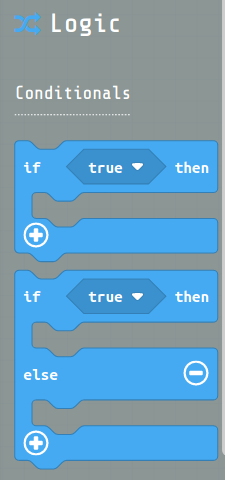

Description: Logic (Conditionals) give the ability to make decisions based on certain conditions so that of multiple outcomes may occur.

-

Why is it needed : Logic / Conditionals are a key concept in interactive media as it allows for different things to happen based on different input choices from the user / player. Or in games to respond to different conditions of play in the game.

-

How it happens in practice: There are logic blocks in MakeCode which express different pathways using the if / then / else logical pattern. Comparison blocks let you compare the values of mathematical and text values and then run different blocks of code depending on the result.

- Examples in our Game Patterns: Animate your Player's Movements

-

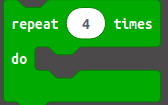

Description: A loop is a way of repeating a piece of code so that it runs more than once.

-

Why is it needed : We could programme an enemy to move 100 pixels to the right, wait 0.2 seconds, and then to repeat the action – moving another 10 steps, and waiting another 0.2 seconds. What if, instead of a single repetition of the action, we want the enemy to move and wait three more times? We could easily add more move and wait blocks. But what if we wanted to repeat the process 100 or 1000 more times? Loops are a way to run the same sequence many times.

-

How it happens in practice: in Make Code we use green Loops blocks to repeat code. An example is the "repeat x times" block.

- Examples in our Game Patterns: Add Static Enemies,

-

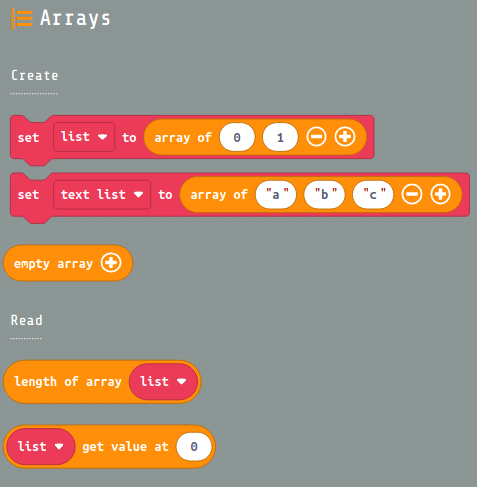

Description: Arrays are a kind of list which also allow you to store and retrieve values but as a flexible collection of numbers or strings or images.

-

Why is it needed : Arrays are commonly used in combination with loops, to loop through a list of things to repeat a process. An example would be the way a tile map is turned into a game layout.

-

How it happens in practice: There is a group of code blocks in the advanced section of the Arcade MakeCode interface which help us to work with Arrays.

- Examples in our Game Patterns: Change Design of Levels

These wider patterns and concepts are a way to learn about wider computing practices that are also applicable beyond the world of making games especially in Interactive Media Design.

-

Description: Also known as States, this pattern is useful when you want one part of your programme to listen out for changes in the stage of another. An example would be listening for an overlap between the player and an enemy. The programme can then take action when this overlap change happens or a particular condition is true.

-

Why is it needed : In many media programmes you need to change formatting or to make something happen based on the conditions of other objects.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

- listening for the player being in a condition of overlap with an Enemy

- changing the animation of a player based on if they are still, moving or jumping

-

Description: Also known as an event handler. Events – one thing causing another thing to happen – are important to interactive media like games. For example, a button triggering the start of play, or controlling game player' s movements.

-

Why is it needed : Working with User Input is a key part of most computer programming design, it allows the user to interact with the programme to make things happen.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

- controlling the player movements on screen

- responding to button presses for jumping for firing etc

-

Description: Also known more generally as separation of concerns, this is a specific example of the computer programming principle that elements that do different jobs should be apart.

-

Why is it needed : In many examples this separation allows editors of the project to make changes to the data easily without worrying about the formatting.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

- using tilemaps to represent level layout

-

Description: Also known as abstraction and decompostion (by modularisation), this is a pattern that allows programmes to be broken down into smaller pieces, which do a specialist job. In this case the pieces are called functions.

-

Why is it needed : The concept is in line with a programming principle called DRY (Don't Repeat Yourself). It allows you to call the same piece of code from different parts of your programme so you don't have to repeat them in more than one place.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include: - creating levels on start and when goal is reached

These ideas are common in the area and Systems Thinking.

-

Description: This concepts allows you to break down a system into its different parts. In our game we can break down the into game components, goal, space, rules and mechanics. This helps to start to identify the different kinds of links between the system elements.

-

Why is it needed : This process of recognising and naming the system elements is the start of being able to understand how a system works.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

- naming the components, rules, space, mechanics and goals of our starting platformer

- the process of making changes to these game elements

-

Description: Links between systems elements can be static or dynamic. The idea of stocks and flows is important. For example in a game you can have a static number of hazards that never changes, or a dynamic population of enemies that may increase or decrease. The nature of relationship between enemies and player will then be different.

-

Why is it needed : Recognising dynamic parts of game system allows you to make more informed decisions about how it will change and react to changes. For example understanding these dynamics are important when making a game to make sure the level of challenge for the player is suitable.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include: - increasing the number of enemies to increase challenge

-

Description: Feedback loops can be balancing or reinforcing. We can thing of a reinforcing loop as change that gets progressively either bigger or smaller. For example a population of rabbits spiralling larger and larger in a place where they have no natural predators and plenty of food.

-

Why is it needed : In a game you may want a reinforcing loop if you want to increase the challenge for a game. For example, you may want the number of enemies to drastically increase towards the end of a level.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include: - creating a hectic game with many spawning enemies

-

Description: Feedback loops can be balancing or reinforcing. Balancing feedback loops tend to react to changes in a system with a responding change that brings balance back.

-

Why is it needed: In eco-systems balancing loops work to keep a system stable, preventing there from being too many predators for example, as they will die off if there isn't enough food for them to prey on. In games balance is needed to maintain the right level of challenge for the player.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include: - gravity acting as a balancing force to jump velocity - keeping a check on the number of enemies that the player has to face so that the game doesn't become impossible

This adaptation of design-based concepts to game making is inspired by the computational thinking definition of Brennan and Resnick.

-

Description: The process of remixing a game involves decisions to change the game intentionally in minor or more fundamental ways. These moments of participant initiative draw from and build on existing knowledge.

-

How it happens in practice: Example activities which demonstrate this include:

- Invitation to peers to set new goal or revise existing goals

- Participants expressing new goals to include in game or around the wider making experience

- Clarification or questions about desired game design behaviour

-

Description: Designing a project is not a clean, sequential process of first identifying a concept for a project, then developing a plan for the design, and then implementing the design in code. It is an adaptive process, one in which the plan might change in response to approaching a solution in small steps.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

- Small revisions to address the game pattern being worked on or sub goals

- Changes which seeking to maintain or create game balance for suitable challenge level

- Evaluating aesthetics of graphics / sound elements and revising further

Various testing and debugging practices are possible from learning to scan block code for error messages, to using tools to watch variables.

-

How it happens in practice: Debugging involves different strategies for dealing with different kinds of errors including:

- Glitches - code still works but unexpected result (questioning

- No errors blank screen, no idea (often retrace steps, go back to earlier version, or have to start again)

- Clues, greyed out code, red dots, error messages (try to narrow down issue, remove sections of code, again go back, try to find duplication of code blocks)

Game testing can be of one's own game or as 'playtesting' of playing each other's game and giving and recieving feedback on game play.

- How it happens in practice: Example activities which demonstrate this incude:

- Expression of pride, or fun when playing own game

- Imagining the user's experience of playing their game

- Giving or receiving feedback either spontaneously or with support form a feedback / playtesting sheet

-

Description: Building on other people’s work has been a longstanding practice in programming, and has only been amplified by network technologies that provide access to a wide range of other people’s work to reuse and remix. This behaviour may be remixing the work of others or through helping others to replicate their own work.

-

How it happens in practice: Example activities which demonstrate this incude:

- Direct copying of game features from other games by replicating code

- More indirect copying of features and ideas via observation or conversation with peers

-

Description: Where participants work together on game making as pairs or in family groups particpants often demonstrate behaviour which encourage collaboration and participation in the broader community aspects of game making. These may come naturally or may be more deliberate as a strategy to enhance learning potential.

-

How it happens in practice: Example activities which demonstrate this incude:

- Redirection of other participant's activity back to reflect their earlier goals

- Invitation to imagine the end game player’s experience

- Advancing or suggesting alterations to collaborative working practices

-

Description: The process of making work public or sharing a 'finished' version with the group is a key part of the design process. The process can support development of the key skills of validation and evaluation.

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

-

Creating a public link from a game making workspace

-

Sharing a project for playtesting or evaluation

-

Requesting or providing formative feedback on a game project

21st Century Skills including Digital Literacies There certain elements of key 21st Century Skills like communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity are covered the design practices. Others are included here.

The topic of digital and web literacy is broad. The web literacy project by Mozilla maps it well. Certain very specific digital skills that are well suited to the kind of collaborative and digital game making outlined in this programme are included section.

-

Description: The process of working on a joint project involves the development of shared understanding of the problem being worked on. This may involve checking working concepts by advancing them and questioning meaning of other's expression. Related activities also include

-

How it happens in practice: Examples include:

-

Asking or providing clarification of terms being used

-

Requesting or offering help in solving problems using specialist terms

-

Description: Problem solving and developing understanding develops some of the aspects of collaborative work to working processes or domain knowledge.

-

How it happens in practice: Example behaviour includes:

-

Giving explanation for outcomes or tactics

-

Applying existing knowledge to the problem at hand

-

Striving to understand project concepts

-

Linking project experience to wider learning

-

Description: The process of offering, providing or requesting help with the non-technical aspects of advancing the project in question. There are other aspects of support which are needed outside of the session like access to resources or helping participants to access learning in a general sense. This is often the role of parents but sometimes siblings or child participants step into this role.

-

How it happens in practice: Example behaviours include:

-

Emotional support through general encouragement and keeping a sense of perspective

-

Brokering access to learning opportunities

-

Procuring resources to support fellow participants

-

Description: The detail of moving from website to another, especially when keeping several browser tabs open, offers the

chance to learn and share a variety of practices which make up key web-navigation literacies. This is an area where young people often are able to help adults. -

How it happens in practice: Activities include:

-

Asking or offering help in navigating between websites or browser tabs

-

Parents or siblings as a repository for the logins and passwords of their children

-

Description: The process of keeping a track of different versions of your work is called version control. There are many ways of doing it but doing it in a manually to keep track of changes to our game is a great way to start to understand the value of this process. The way MakeCode doesn't support log ins encourages a process of saving versions of your work frequently and saving them in a document, say an online google doc with dates and descriptions.

-

How it happens in practice: Example behaviour showing this skill includes:

-

Encouragement between participants to save work

-

Keeping written records of changes

-

Deciding to create a new version of work

-

Explaining and reminding peers of value of version control