Rigorous Preprocessing and Sentence Encoding NLP Algorithm

Documentation

The prompt for the 2020 Ignition Hacks Sigma division was to perform sentiment analysis on a random selection of tweets, with the goal of creating a machine learning model to find if tweets carried positive or negative sentiment. This is a binary classification problem involving natural language processing, with 1,000,000 labeled data points available for training and validation, and 600,000 unlabeled data points which are used to judge models.

- Python

- Tensorflow

- Numpy

- Pandas

- NLTK

To Use: Run Main.ipynb with training and test sets from the following folder: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1OAKLPqU0JVXURqPnvESMhbkNildVIzoc?usp=sharing

The first part of creating a model to perform natural language processing was to decide on the tools. By the rules of the competition, Python was required to be the only allowed programming language. Due to the large amount of online resources, as well as past experience from group members, it was decided that Tensorflow was to be used to construct the model, utilizing additional Python data science modules such as pandas and numpy. The scikit-learn model was not used due to the smaller amount of experimentation and customization which could be done in terms of the model layers. In addition, while pretrained models such as RoBERTa would likely provide superior results to raw Tensorflow code, the training time would be beyond the limits of the hackathon and the available resources, and freezing the layers would go against the rule of not being allowed to use data from outside the hackathon.

The large amount of training data, as well as the lack of sentiment clarity in many tweets (as manually observed), led us to use deep learning models, with a larger number of deep learning layers. This would allow the model to learn more subtle patterns within the data, and make full use of the dataset.

Due to there only being one feature, the tweet itself, it was difficult to collect information about the dataset without using natural language processing tools. It was, however, noted that in the training data, there was an exact 50-50 split between tweets which were labeled to be of positive sentiment and tweets of negative sentiment. Therefore, it was decided that the split between training and validation data would be done at random, with approximately 15% of the data set to be validation data and the remaining 85% to be training data.

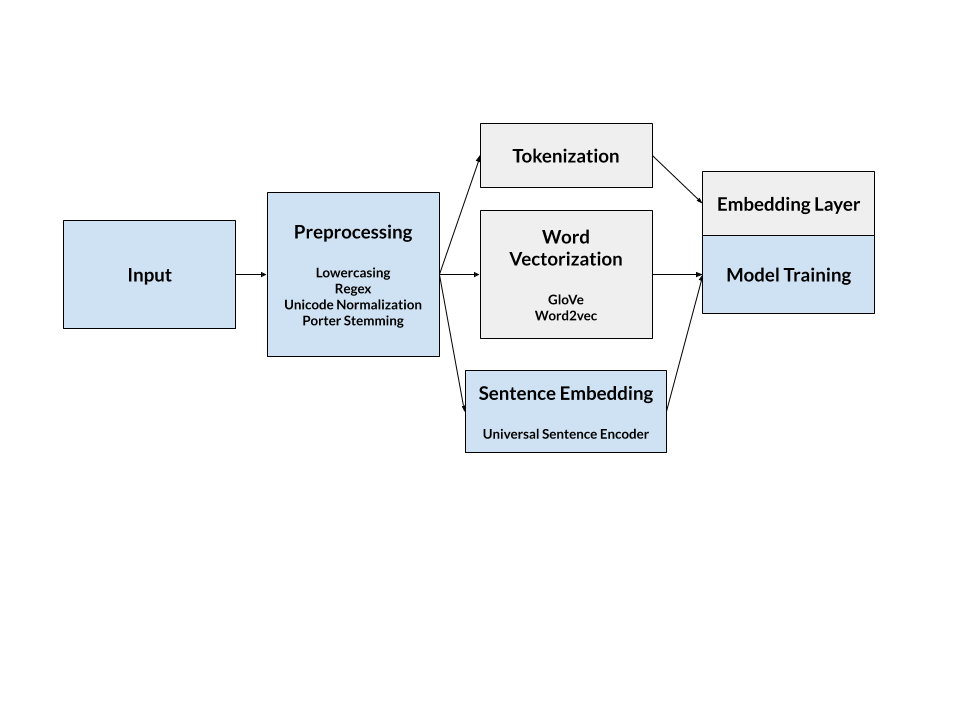

Due to the nature of tweets and other fast text message based communication, it was imperative that preprocessing was necessary for effective natural language processing (NLP) and deep learning.

The most fundamental and perhaps most effective approach is lowercasing all the text data. Although this technique is more useful with sparse instances of words in smaller datasets, lowercasing still proved beneficial by improving validation accuracy by approximately 1% to 3%.

Tweets often contain expressions that may not contribute to the overall sentiment, such as user handles (@janedoe), hashtags (#ignitionhacks2020), and links (www.ignitionhacks.org). These expressions often contribute to greater noise in the dataset since many require additional context, such as understanding a user’s history or reading what is on the linked webpage, to provide a substantive sentiment relation. It is important to note that, in this dataset, it was found that hashtags were beneficial for understanding sentiment, at least by an empirical measure of the accuracy metric. A possible hypothesis is that certain emotions were associated with these tags, and could in fact be used for sentiment analysis on its own. Regex was used to clean up the data by removing handles and links, as well as punctuation and numbers.

To further reduce noise and improve sentiment analysis performance, stopword removal, normalization, and stemming was used. The English language contains many short and common words that do not give additional context for NLP, such as ‘a’ or ‘the’. These stopwords were removed by tokenizing the sentences and checking for matches against a list provided by NLTK. To keep normalization times low, a simple NFKD (Normalization Form Compatibility Decomposition) unicode normalization was implemented to remove special characters. Afterwards, the Porter stemming algorithm reduced words to their root form, allowing for more consistent sentence encoding.

Perhaps the most crucial portion of the algorithm’s preprocessing is text enrichment using techniques such as word and sentence embedding.

Most NLP algorithms utilize a basic tokenization and a pretrained embedding layer such as ‘keras.embedding’. In order to improve upon this and create a model that could be effective on different types of text data, word vectorization and sentence encoding was tested. Both methods convert strings of text into vectors of floats based on semantic similarity, given by techniques such as cosine or euclidean distance. This is superior to conventional embedding layers as it gives a measure of semantic similarity between different words in the case of word embedding, as well as word-sentence context in the case of sentence embedding.

A disadvantage of using word embedding is losing context and thus being susceptible to spelling mistakes, expressions that require multiple words, abbreviations, and words with similar meanings. After testing, sentence encoding proved to be a better approach, and consistently provided close to a 2% increase in validation accuracy compared to the same model with default keras embedding. However, it must be noted that these encodings came at the cost of long run times and there are also averaging techniques to create contextual relationships between word vectors. Nonetheless, it is important to focus on the real strength of sentence encoding, which is providing associations between words such as “Ignition Hacks” and “Hackathon”, as well as greater flexibility for the model to handle new data or train on other languages.

A variety of models were created and tested on the training data, such as one with only dense and dropout layers, a convolutional neural network, a bidirectional long short-term memory (LSTM) network, and a gated recurrent unit (GRU) neural network. These were all trained for 5 to 40 epochs, depending on the time it took for them to finish each epoch, and each of their layers were tinkered with, such as by adding dense layers and dropout layers, and changing parameters such as the number of nodes in a layer or the activation function used. These neural networks were tried with the Keras tokenizer, as well as with the encoded data which was created with the Universal Sentence Encoder.

The first model created used only dense and dropout layers, and used the following code:

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Embedding(vocab_size, 16, input_length=max_len),

tf.keras.layers.GlobalAveragePooling1D(),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.3),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.5),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')When using the pre-encoded data, the first two layers must be removed; otherwise, they are necessary for the model. Dropout layers (layers which disable certain layer outputs at random) were chosen to reduce overfitting, and the associated input disable rate was experimented with. Additionally, it was found that for this problem, which is binary classification, the optimal final layer was a dense layer with a sigmoid activation function; however, for the intermediate dense layers, it was optimal to use the relu or tanh activation functions. Both of these were experimented with, but did not yield a significant difference in validation accuracy. The training accuracy and validation accuracy of some of the models using this structure are shown in the graphs below:

Hyperparameter tuning suggested that smaller batch sizes (i.e. 16) were favourable for minimizing validation loss. The models were prone to overfitting, so hidden layer units were decreased and depth was also decreased to two. L2 Regularization was added to apply a penalty on losses and proved to be highly effective in delivering more consistent results and preventing overfitting within the specified epochs.

However, our model was constrained by the optimization techniques available to the Tensorflow API, as well as limited data for training. While pre-trained models and other transfer-learning approaches from robust NLP models already had optimized pre-training hyperparameters tuning approaches, they require immense resources to train (with runtimes well beyond the scope of this hackathon) or result in using pretrained weights and biases that have already exhausted large external datasets outside of the hackathon and will deliver preeminent results by simply applying the model on the given dataset.

Another model which was tested was the convolutional neural network (CNN), which functions by applying a convolutional layer over areas of the input data to find important features and patterns in the data. The associated code is shown below:

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Embedding(vocab_size, 16, input_length=max_len),

tf.keras.layers.SeparableConv1D(16, 5, activation='relu', bias_initializer='random_uniform', depthwise_initializer='random_uniform', padding='same'),

tf.keras.layers.GlobalMaxPooling1D(),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(128, activation='relu'),

tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.5),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')

])A bidirectional long short-term memory (LSTM) model was also created, using the following code:

model = tf.keras.Sequential([

tf.keras.layers.Embedding(vocab_size, 16, input_length=max_len),

tf.keras.layers.Bidirectional(tf.keras.layers.LSTM(16, return_sequences=True)),

tf.keras.layers.Bidirectional(tf.keras.layers.LSTM(16)),

tf.keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid')

])Unfortunately, since both the CNN and bidirectional LSTM models took a long time to train without a large number of layers (such as additional intermediate dense and dropout layers), it was unfeasible to train them for many epochs. The graph plotting training accuracy and validation accuracy against the number of epochs for the CNN is shown below:

In order to possibly receive more accurate predictions, an ensemble of different models could be used. They would be able to make predictions on each test tweet, and the results could be averaged to find a hopefully better estimate of the tweet sentiment by reducing the effects of individual models overfitting. A limitation which we faced, however, is that the short timespan of the hackathon did not allow for adequate training of some models, and this step would require additional computational resources and time to do.

When looking at the training graphs for many of the models, the validation accuracy appeared to level off, while the training accuracy continued to increase. This is classic overfitting, and was manually solved in our case; however, this could also have been solved more efficiently using early stopping, which can be done using the tf.keras.callbacks module to save past models in a H5 file before reverting to the model which was least likely to be significantly overfitted.

Distributed under the MIT License. See LICENSE for more information.

- Thank you to Ignition Hacks 2020 for a wonderful challenge and experience!

- Tensorflow Hub for Universal Sentence Encoder

- KDnuggets for NLP preprocessing background information: https://www.kdnuggets.com/2019/04/text-preprocessing-nlp-machine-learning.html

- Udacity for Intro to TensorFlow for Deep Learning Course