As part of the project "Mining and Modeling Text" project (University Trier, Germany), several controlled vocabularies have been created. When generating statements, these are used to standardise information from different sources, to make it queryable and comparable. Here you can have a look at the module "terminology", which defines the modelling of the vocabularies in our ontology.

In general, the vocabularies serve the project goal of making information extracted from three different types of sources linkable and available in a publicly queryable knowledge network. In this context, the elements of the vocabularies play an enormously important role as connecting concepts. They increase the comparability between heterogeneous statements in the different types of sources. Above all, however, they are the key to 'LODification', i.e. the semantization of the information extracted from the three source types in the form of strings, and thus not only make the statements linkable to one another, but also integrate them into the Semantic Web.

Controlled vocabularies are thus the interconnecting point that links the semantic content from three different source types and, in addition, connects them to external resources. The strategies for building the five different vocabularies are, like the vocabularies themselves, very heterogeneous and adapted to the respective requirements arising from the three source types: metadata from a bibliography (Martin / Mylne / Frautschi 1977), statements from scholarly publications on the history of literature (such as literary histories and scholarly articles), and semantic and formal characteristics of primary sources (such as novels). Central to this is that we extract and link data mostly 'bottom-up' from those sources. The elements of the vocabularies can therefore be understood as semantic intersections between what we find in or can extract from the different source types (see "Our Approach"). The aspects outlined below are in part generally relevant to the construction of vocabularies in the context of the Linked Open Data paradigm, but are in part also dependent on the project context in the specific design and associated decisions. The elements of vocabularies play an important role in our approach to an 'atomization of literary history'. In the sense of a new scalability, we accept reduction of complexity in order to open new perspectives for literary history within the framework of a data-based approach to literary history on the basis of larger amounts of data. The loss of precision must always be balanced and it has to be weighed up which granularity and semantic precision can still be valuable for users without making too many compromises in the comparability of data.

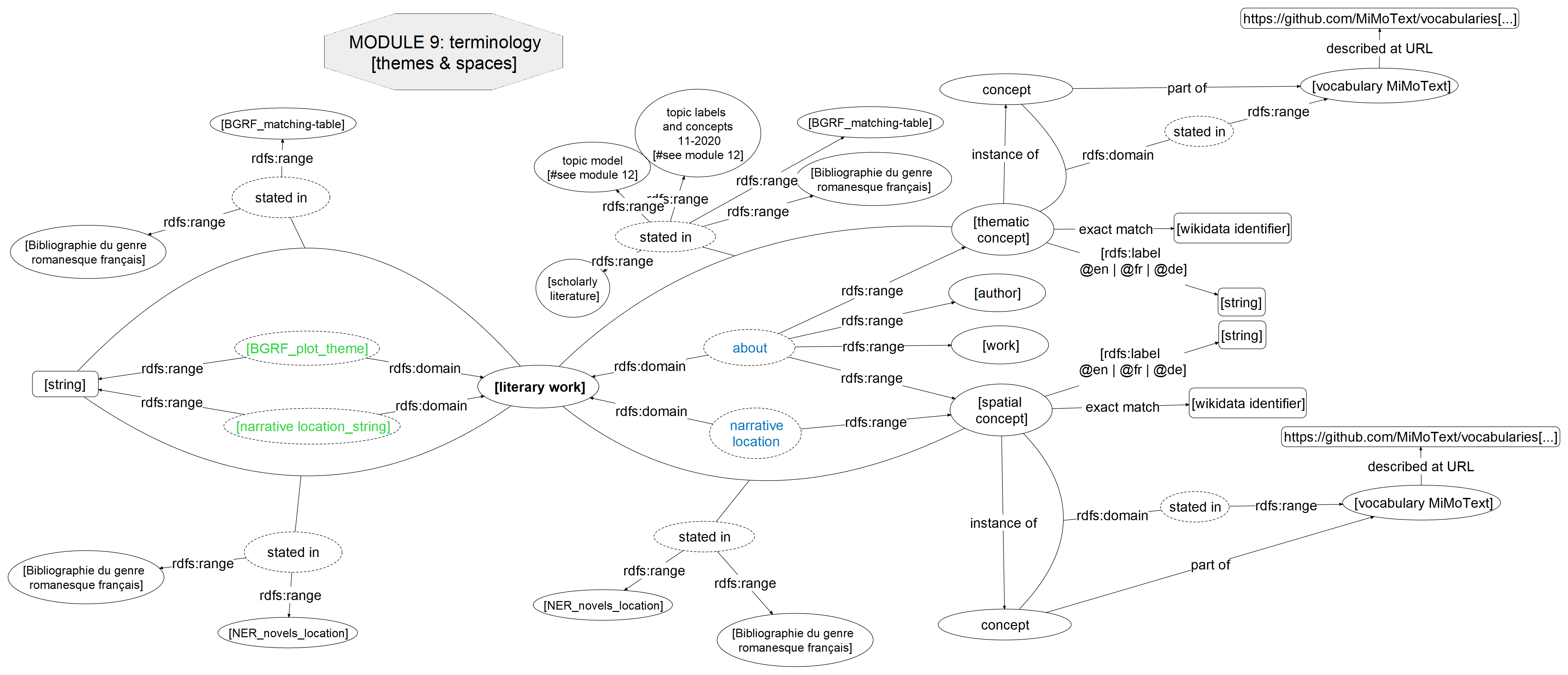

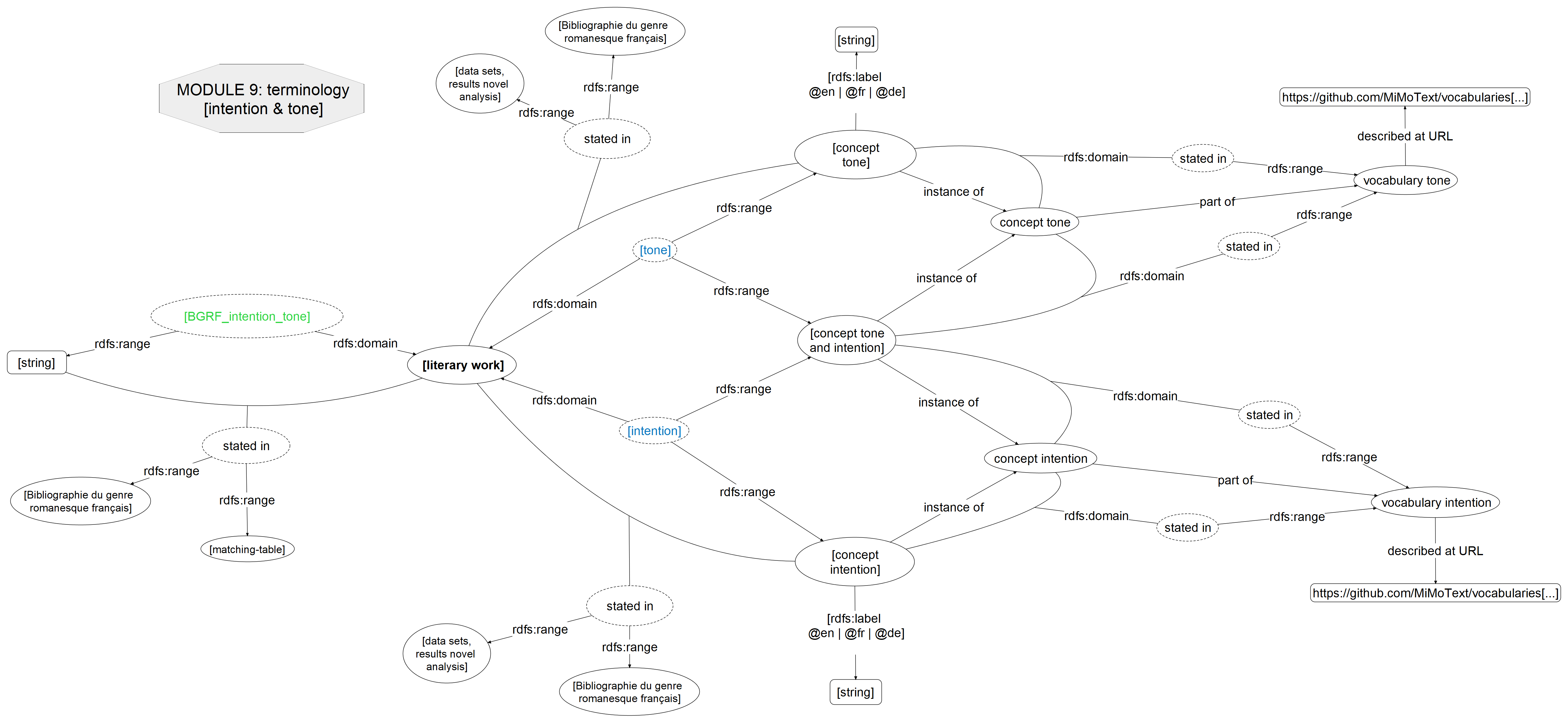

The vocabularies in MiMoText are very heterogeneous, among other things with regard to the number of elements and granularity, the specificity / distinctness of the domain reference. We have abstracted from this heterogeneity for the purposes of reusability in the module 9 "terminology" of our ontology which defines the overarching modeling approach for the vocabularies. In the two following more detailed visualizations, specific particularities are illustrated in each case:

- Module 9 - themes and spaces: Here, the linking of individual properties with only one vocabulary (narrative location) or several vocabularies (about) in the rdfs:range becomes clear.

- Module 9 - intention & tone: This shows that there is an intersection of the two vocabularies, in other words that some concepts are elements of both the intention and the tone vocabulary and are therefore in the rdfs:range of both properties (see discussion of intersections below).

In the sense of reducing complexity, we have refrained from creating over- and sub-terms in the form of a thesaurus. Basically, the focus of the project is not to develop a (as semantically precise or differentiated as possible) vocabulary, but to link very heterogeneous data in the Linked Open Data paradigm.

In general, whenever it was reasonable (with a correspondingly necessary broad interpretation of the concepts and acceptance of imprecision), we linked our concepts to the corresponding concepts on Wikidata using the "exact match" property reused from Wikidata. Partially, we have linked to Wikidata concepts as “close match” as we could not see an alignment to “exact match”. Reasons for this were: (1). There was too little information of the concept on Wikidata overall, so that it is semantically underdefined. In other cases there was ‘too much information’ (in the description as well as in the semantic ‘storage’ of the "also known as" of the infobox) that went in a semantic direction that was too narrow compared to our use of the concept. (2.) If the concepts were semantically too rich and / or specific, then we refrained from mapping because the consistency was to low. This is especially true for concepts in vocabularies with few elements ('tone', 'intention'). (3.) In further cases we observed inconsistencies between the informations provided in the different languages. Thus, we decided to use "close match" when we found a clear discrepancy in one of the three languages relevant to us with the semantic filling in the other two languages. So when the label in one of the languages relevant to us did not adequately represent the semantics of the concept we did not use “exact match”. We have based this on a broad semantic interpretation, since certain tensions between the scope of a concept always varies slightly between languages.

We have two French resource types - the bibliography and the novels themselves - as well as the German-language scholarly literature. This already resulted in bilingualism, which we extended to include English, and all vocabularies are thus trilingual.

In our domain of knowledge, there are no standardized vocabularies and also relatively little consensus on theoretical foundations. This poses particular challenges with regard to vocabulary construction, since we have the claim that the specialist community of literary scholars will find the selection processes and accentuations in the modeling or semantization of concepts plausible and that their research will gain new perspectives as a result.

References and further information

Martin, Angus, Vivienne Mylne, und Richard L. Frautschi. 1977. Bibliographie du genre romanesque français, 1751-1800. London: Mansell.

Schöch, Christof, Maria Hinzmann, Julia Röttgermann, Anne Klee, und Katharina Dietz. 2022. „Smart Modelling for Literary History“. IJHAC: International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing [Special issue on Linked Open Data] 16 (1): 78–93. https://doi.org/10.3366/ijhac.2022.0278.

Hinzmann, Maria, Matthias Bremm, Tinghui Duan, Anne Klee, Johanna Konstanciak, Julia Röttgermann, Christof Schöch, and Joëlle Weis. “Patterns in Modeling and Querying a Knowledge Graph for Literary History [Preprint].” Zenodo, June 18, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12080340.

See the Comparing section in our SPARQL-Tutorial

The thematic vocabulary is a controlled vocabulary for assigning topics to thematic concepts. It is used to create thematic statements and feed them into our knowledge graph. The base is a list of terms from the Dictionnaire européen des Lumières, which is supplemented by thematic keywords from the Bibliographie du genre romanesque français (BGRF; Martin / Mylne / Frautschi 1977) and thematic keywords identified during the manual annotation of the secondary literature as well as the labeling process of the Topic Modeling.

The vocabulary currently also contains concepts for which there are no statements within the MiMoTextBase yet, but which we can offer connecting points for other projects, due to the close reference to the epoch- and domain-specific as well as very extensive initial resource (Delon 2007). The "source" column documents the source from which a concept originated if it does not belong to the initial resource. The initial resource also contained spatial concepts that we extracted and integrated into our spatial vocabulary. Since spaces can also function thematically, the rdfs:range of our about property is modeled accordingly (cf. Module 1: Theme ).

References and further information

Delon, M. (Hrsg.). (2007). Dictionnaire européen des Lumières (3. tirage). PUF. Martin, Angus, Vivienne Mylne, und Richard L. Frautschi. 1977. Bibliographie du genre romanesque français, 1751-1800. London: Mansell. Klee, Anne, und Julia Röttgermann. 2022. „“Nuit, correspondance, sentiment” - Topic Modeling auf einem Korpus von französischen Romanen 1750-1800“. apropos: Perspectives on Romania. Romanistentag 2021, Sektion Digital, global, transdisziplinär: Impulse für eine transdisziplinäre digitale Romanistik. (9): 57–86. https://doi.org/10.15460/apropos.9.1888.

Röttgermann, Julia, Anne Klee, Maria Hinzmann, und Christof Schöch. 2022. „Literaturgeschichtsschreibung datenbasiert und wikifiziert?“ In DHd2022: Kulturen des digitalen Gedächtnisses. Konferenzabstracts, herausgegeben von Michaela Geierhos, Peer Trilcke, Ingo Börner, Sabine Seifert, Anna Busch, und Patrick Helling. Potsdam. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6328157.

See the Themes section of our SPARQL-tutorial

The spatial vocabulary has the particularity that its elements can be located at the object position (rdfs:range) of different properties (rdfs:range): besides 'narrative location' also 'place of publication' and 'about'. The vocabulary is based on narrative locations under the keywords of the bibliography, the places of publication of the novels, and the results of Named Entity Recognition on the full texts of the roman18 corpus. Originally, the starting point was the spatial concepts from the Dictionnaire européen des Lumières (Delon 2007, see "Thematic vocabulary".)

In the process of reducing complexity, we have refrained from drawing a semantically precise intermediate level between real locations and the concepts of these locations in narrative texts. We also did not differentiate between 'mentions' and actual 'narrative locations'. The spatial concepts annotated by the bibliographers (Martin / Mylne / Frautschi 1977) have the quality of actual narrative locations. In the Named Entity Recognition results there are also such spatial concepts which are simply mentioned but do not constitute the location of the plot. For the construction of the vocabulary we performed a reconciliation to Wikidata with OpenRefine.

References and further information

Hinzmann, Maria, Julia Röttgermann, Anne Klee, Moritz Steffes, und Christof Schöch,. 2022. „The French Enlightenment Novel as a Graph? Potentials and Challenges in the Construction of a Knowledge Network (extended abstract)“. https://zenodo.org/record/5840089.

Röttgermann, Julia, Maria Hinzmann, Henning Gebhard, Anne Klee, Johanna Konstanciak, Schöch, Christof, und Moritz Steffes. 2022. „Mining and Modeling Spaces and Places for Literary History as Linked Open Data“. In DH 2022 - Conference Abstracts, herausgegeben von Ikki Ohmukai und Taizo Yamada. Tokyo: DH2022 Local Organizing Committee. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6948236.

In the first keyword position of the bibliography (Martin / Mylne / Frautschi 1977) there is a huge variety of strings about the narrative perspective respectively narrative form. They can be very short like just “3e personne” or “dialogue” but also combinations like „3e personne avec dialogues et récit 1re personne“ or „1 re personne, mémoires en une série de lettres, avec récits intercalés 1re personne“. It has been challenging to build up the vocabulary and map this variety to its six elements. The starting point for the 6 categories is the standard work by Genette (1979) with his categories established there, which have been adapted (and that also means: partly reduced, partly extended) for the domain of Computational Literary Studies by Calvo Tello (2021). The adaptation is accompanied by semantic shifts, in particular the understanding of 'homodiegetic', which is to be read as homodiegetic-non-autodiegetic (1st person, for more details see module 3), that is, a specific set of homodiegetic narratives that are not autodiegetic. In Genette, homodiegetic is actually the supercategory, so the specific use of 'homodiegetic' for a subset needs to be emphasized at this point. One goal, in addition to the LODification of these strings, was that we could use the extracted statements to balance our roman18 corpus so that there would be a representative set of epistolary novels, for example. We discussed several approaches like multilabeling with these 6 categories as well as combined labeling with different properties like ‘dominant narrative form’ and ‘narrative form’. These approaches would be contrary to our balancing goal, because it doesn't help if everything is 'mixed'. Consequently, the category "mixed" is only chosen when there are several narrative forms of equal value or when it is not possible to decide, for example when the string is “1re personne et 3e personne”. All other categories are chosen when one narrative form dominates. To make everything transparent for the users we have the property narrative form string in addition to the narrative form property, which makes the original value from the bibliography exactly traceable.

References & further information

Calvo Tello, José. 2021. The Novel in the Spanish Silver Age: A Digital Analysis of Genre Using Machine Learning. Bielefeld: transcript.

Genette, Gérard. 1979. Narrative Discourse: Gerard Genette. Oxford: Blackwell.

The first few steps consisted of sorting through the French term lists, splitting and then mapping them to fitting concepts of intention and tone. The word lists stem from the (fourth and) fifth column of descriptions in the BGRF in which the authors categorized the œuvres. However, both columns are not completely harmonized and needed to be split up and reclassified. Accordingly, for tone, we composed concepts like 'satire’ or ‘ton léger’; for intention, equally, concepts such as ‘intentions moralisatrices’ or ‘considérations politiques’. From the list that consisted of 389 entries without duplicates, frequencies and adequacy for the corpus determined whether a word would form a concept or be mapped to one as a variant. Unique entries or those not fitting the category did not make it into the final list.

Afterwards, as an intermediate step, we proposed 32 and 19 concepts with different numbers of string variants for each of the two subcategories of intention and tone. Simultaneously, we mapped those concepts to the German ones that were previously manually extracted from scholarly publications in order to grasp even more solid concepts. During the multilingual mapping process, we clustered terms that describe the same concepts. Simultaneously, we generated a matching table for both intention and tone, in which we outlined a global structure of main concepts and corresponding sub-terms that occur in the fifth column.

To be able to find inspiration for solid concept descriptors that represent the novels in the corpus, we did a reconciliation with OpenRefine on the Wikidata data repository. Here, we tried to find matching entries to the concept vocabulary in English, German and French. Moreover, we were able to obtain further information on the concepts, such as the Wikidata ‘instance of’ attribute or descriptions of the entries in the different languages. However, not all words from the concepts had a match on Wikidata and often, the proposed matches seemed not quite adequate for our purpose. That is the reason why we only used this reconciliation experiment as an intermediate step and inspiration for additional solidification and translation.

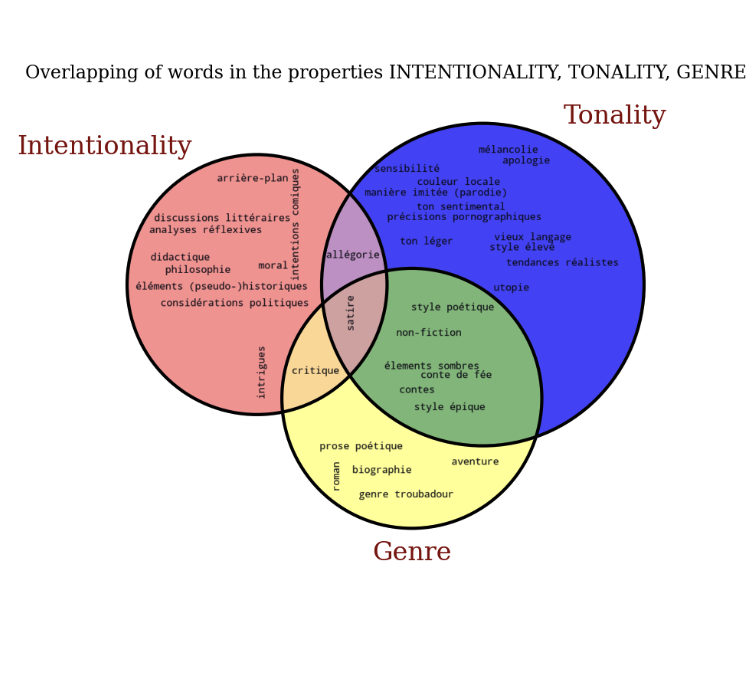

Additionally, this led to a new question: Should we include a third concept in this category, namely ‘genre’?

A Third Concept?

As mentioned beforehand, the Wikidata reconciliation led to the question whether another concept could be necessary. Since the mapping with entries in Wikidata showed that quite a lot of the concepts are of instance ‘literary form’ or ‘XY genre’, we considered broadening the horizon of the controlled vocabulary. For this, we mapped the vocabulary to the two original concepts, ‘intention’ and ‘tone’, plus one new concept, temporally namely ‘genre’; following with a calculation of the intersections between these three and their included sub-terms. In the following image, a Venn diagram shows how they merge together and how unique each of them are.

Figure: Venn-Diagram showing the intersections of the vocabularies

Since the category ‘genre’ contains the fewest unique entries, which we thought could not be categorized as either ‘intention’ or ‘tone’, we decided against including it in the vocabulary conceptualisation. A brief outline of the background to the considerations: The bibliographers do not have a consistent category system for the different keyword positions and 'genre information' is stored in all positions. The modeling of 'genre' cannot be limited to information from the 5th keyword position and would have to be matched and modeled separately and in relation to the other keyword categories in an elaborate process. This would include the alignment and creation of new matching tables with the relevant concepts in the scholarly literature, which we have not yet realized.

Translation and Final Concepts

In a final step, we translated the French and German terms of the concepts for both ‘intention’ and ‘tone’ to English and transposed it into a fitting export format with which new statements for the knowledge graph can be generated. The results can be found here for intention and here for tone.

All vocabularies are in the public domain and can be reused without restrictions. We don’t claim any copyright or other rights. If you use our vocabularies, for example in research or teaching, please reference this collection using the citation suggestion below.

MiMoText/vocabularies, edited by Anne Klee and Maria Hinzmann, with contributions from Sarah Heintz, Johanna Konstanciak, Sarah Rebecca Ondraszek, Julia Röttgermann and Christof Schöch. Trier: TCDH, 2023. URL: https://github.com/MiMoText/vocabularies.

- MiMoTextBase - a knowledge graph on Eighteenth Century French Novels

- MiMoText SPARQL endpoint (Query Service) and Example query: Overview of our controlled vocabularies

- [MiMoTextBase Tutorial: How to query the graph and an introduction to SPARQL] https://docs.mimotext.uni-trier.de)

- MiMoText ontology