A standard to settle Ethereum smart contracts fairly in case of vulnerabilities.

An estimated 3 million ETH (350 million USD) are locked in vulnerable smart contracts today. Fortunately, only 0.30% (9,094 ETH, or approximately 1 million USD) has been claimed by attackers, but smart contracts continue to be attacked on a daily basis [1]. In this paper, we present a novel scheme to incentivize the responsible disclosure of smart contract vulnerabilities. We introduce a game (0xdeface.me) that incentivize a) security researchers to disclose vulnerabilities to contract operators instead of draining their funds; and b) contract operators to release a reward when a security breach is found and safely destroy contracts by returning funds to the stakeholders. We think this will transform smart contract security by changing the model from a negative-sum game to a positive-sum game. The goal of 0xdeface is to make Ethereum more secure by mitigating the impact of smart contract vulnerabilities, hence increasing the adoption and implementation of smart contracts to manage funds in a decentralized fashion.

Smart contracts represent a paradigm shift in programming, enabling the permissionless and transparent transfer of monetary value. This has only been practically possible since the launch of Ethereum. Since smart contracts are still so new, we are still developing best practices, and well-established best practices will take years to stabilize.

In Ethereum, smart contracts are written in Solidity or Vyper, both inspired by existing programming languages: Javascript and Python, respectively. In both cases, the base language was slightly adjusted to provide new primitives to allow the transfer of monetary value possible. This approach has between criticized, however, especially in the case of Solidity, which has faced claims that its design principles were too relaxed for the secure transfer of money. And indeed, Solidity does feature odd design choices: (1) it doesn't have under- and overflow protection, (2) interfaces are not enforced, (3) similar modifiers are easily confused as their naming is virtually indistinguishable, (4) code reuse is implemented through multiple inheritance, a complex pattern that can lead to non-trivial bugs [13], and (5) inline assembly is hard to write, hard to read, and hard to audit.

No one has been surprised that the combination of these design choices, a lack of best practices, and inexperienced developers has resulted in several million ETH being stolen. The most notable incident was in June 2016, when an attacker drained 3.6 million ETH from TheDAO [2], forcing the Ethereum community to hard fork the network to allow TheDAO users to withdraw their funds. Although the situation has improved greatly over the past few years, with (1) the community working together to develop best practices, (2) developers gaining experience, and (3) professional audit firms reducing risks pre-launch, writing secure smart contracts is still a challenge. To this day, even the most experienced teams [12] and their world-class auditors make mistakes [3] and will continue to make mistakes going forward.

To further understanding of this phenomenon and to give proper context, we'd like to highlight the incentives at play. Specifically, we'd like to elaborate on the motivations to attack contracts and how we think 0xdeface.me can improve the situation by shifting from an ecosystem-wide negative-sum game to a positive-sum game.

Each smart contract that stores ETH is essentially a bounty on itself, offering a tempting target for attackers. We expect to see the frequency and ingenuity of attacks on smart contracts increase in the future, as the number of smart contracts grows, the amount of money at stack increases, known vulnerabilities are better documented, and automated auditing suites like Consensys' Mithril [4] and TrailOfBits's ManiCore [5] make finding vulnerabilities easier.

In this section, we discuss why it is (1) seemingly rational for an attacker to target smart contracts, (2) difficult to maintain smart contracts and (3) that this situation leads to a negative-sum game. We conclude that there should be an ERC standard and marketplace for the consensual exchange of vulnerabilities between attackers and contract operators.

To begin, let's discuss why it is seemingly rational for an attacker to target smart contracts.

Since the dawn of Bitcoin and Ethereum, there has been a commonly shared conviction within the community that transparency, decentralization, and permissionless innovation is key to the success of the respective ecosystems. For several reasons, developing a smart contract as closed source is considered a faux-pas: (1) Users should be able comprehend the full functionality of a smart contract (transparency); (2) Nobody must be able to exercise full control over a contract (decentralization); (3) Everybody must be allowed, without the innovate on any part of the infrastructure, without cost (permissionless). For these reasons, it is a widely accepted best practice that smart contracts must be open source. We recognize that security through obscurity is not a viable defence mechanism, but it must be acknowledged that for a smart contract attacker, open source smart contracts lowers the barrier to entry and lets them see what they are attacking.

Over several weeks, 0xdeface used an Ethereum full node to crawl the Ethereum

blockchain and Github to discover newly uploaded smart contracts. By leaving

their /build folder in their GitHub repository, contract repositories could

be found easily by querying for their address using the GitHub search API.

While the setup of this experiment was trivial, it yielded many vulnerable

smart contracts as potential targets. In many cases, Mythril even pointed

toward specific functions and vulnerabilities to exploit [9]. An even simpler

means to search for vulnerabilities is to occasionally review Etherscan's

"Verified Contracts" page [5] for smart contract source code [footnote 1]. The

lesson here is that while open source contracts might lead to greater security

across the ecosystem as a whole, it does not necessarily lead to greater

security for individual contracts.

Once an attacker has access to a contract's source code, they can set up a local environment using tools like Ganache, Truffle and Remix IDE. This local setup is then used to simulate attacks against the contract. If a critical vulnerability is found, the attacker can, given the deterministic nature of Ethereum, confidentially assess whether the vulnerability can be used to drain funds from the main net contract. Using privacy-preserving technologies like TOR, Monero, and Zcash, this makes attacks efficient, cheap, largely anonymous, and therefore rational for an attacker.

Now that we've given reasons that attacking smart contracts is rational, we'd like to elaborate on why it is difficult for operators to maintain their contracts once deployed.

The reason is simple: Smart contracts are immutable. Every contract uploaded to the Ethereum network is assigned an address generated using the deployer's address and a nonce. This address is then used by clients to interact with the contract. Today, Ethereum smart contracts cannot be changed in place [footnote 2]. The options for the contract operator are limited to the following maintenance schemes: (1) Build an upgradeable contract using proxy-patterns or (2) Deploy a revised version of the contract and inform users of the change.

Unfortunately, both options come with significant negatives: (1) An upgradeable proxy contract is inherently not permissionless or decentralized. Though implementation-specific, it likely defines an operator that is able to change the proxy routing such that potentially users' funds could get, in the worst case, stolen. (2) Informing users and updating apps to the newly generated contract address is cumbersome, trust-maximizing and non-scalable. It comes with increased scrutiny by the community, potential loss of credibility and significant cost.

For traditional software, a patch for a vulnerability can be distributed by releasing a new version of the product (that might trigger other auto-update patterns) or, in case of a web application, the fix can be put in production within minutes. Ethereum's immutability makes fixing vulnerabilities non-trivial. For many businesses in the ecosystem, smart contract vulnerabilities might in fact be a worst-case scenario. Maintaining deployed contracts is, and will continue to be, difficult.

This brings us to why attacking smart contracts is currently a negative-sum game. First, we argue why attackers may not be incentivized to attack contracts. Second, we highlight the problems of contract operators suffering an attack. Third, we state the role of the user in the situation.

Attacking contracts, especially ones of well-known projects, often comes with

several negatives for the attacker:

(1) Increased attention by social media and community vigilance can lead to the

attacker being identified and exposed.

(2) By crowd-sourcing the attacker's addresses, stolen funds can be traced and

effectively frozen by exchanges. The stolen ETH is taken out of the circulating

supply, making attacks a negative-sum game.

(3) Stolen funds can most likely not be exchanged into fiat, as most exchanges

require KYC for larger amounts.

(4) An attacker runs the risk criminal prosecution, as stealing users'

funds is very likely an offense in many jurisdictions [footnote 3].

We believe these factors are a big part of why such a small portion of vulnerable funds—only 0.3%—have been claimed by attackers [1].

For a contract operator, the situation is equally tricky. (1) Bounty programs are often run before a contract is deployed. After deployment, the contract quite literally becomes the bounty [8]. (2) As seen recently, audits can only limit the risk of vulnerabilities but not totally eradicate them [footnote 4]. (3) Successful attacks to deployed contracts are often businesses' worst-case scenarios, resulting in the entire project shutting down (see: TheDAO) [2].

Contract users are probably the worst off of all parties. They potentially lose all their funds and often have no way to participate in governance decisions taken by a contract operator under fire. Regulation lags well behind the technology. This results in a lack of accountability. Who's to blame for the loss of user funds? The attacker? The contract operator? The user themselves?

Since stolen ETH is essentially taken out of circulation, we conclude that smart contract security is a negative-sum game. That's where 0xdeface comes in. 0xdeface (ERC-XXXX) is a standard to settle vulnerable smart contracts fairly in favor of users and developers. Auditors confidentially submit disclosures to 0xdeface. Contract operators review disclosures. If the auditor and contract operator agree a critical vulnerability has been found, then a contract can be settled fairly by returning its users' funds. Auditors get rewarded with a bounty held in escrow by 0xdeface's Negotiator.

0xdeface's incentive game consists of multiple components. In this section we define the components and how they form an incentive game.

The Negotiator is 0xdeface's central component. It is an Ethereum smart contract consisting of functions for: (1) an attacker to commit a vulnerability, (2) a contract operator to pay for a vulnerability, (3) an attacker to reveal a vulnerability and (4) a contract operator to decide on a vulnerability. In essence, the Negotiator allows an attacker to confidentially transmit a vulnerability to a contract operator using public-key cryptography (commit and reveal). For a contract operator to view a vulnerability, however, they must send a stake to the Negotiator (pay). If a potential vulnerability has been found, the contract operator must decide to either (decide):

- Shut down the contract, return its users' funds, and send the stake to the attacker; or

- Ignore the vulnerability, sending the stake back to the contract operator.

In the following sections, we argue that the Negotiator incentivizes the fair settlements of contracts.

In the 0xdeface protocol, an attacker is able to submit a hash of their

unencrypted vulnerability report along with their commit. While this doesn't

expose the report, it allows the attacker to prove publicly that they submitted

a legit vulnerability at a certain point in time (time-stamping). If the

contract operator shuts down the contract using a non-compliant procedure, then

the attacker can reveal the content of the time-stamped report and prove to the

world that the operator didn't play the game fairly. We call this scheme Proof

of Attacking.

Another central component is 0xdeface's Exploitable ERC standard. It is an optional interface for developers to implement, potentially preventing their contracts from getting drained. Exploitable currently consists of seven functions:

ExploitableVersion(): Return the version of the incentive gameimplementsExploitable(): Check the contract's compatibilityExploitableReward(): Return the attacker's potential reward in Weipay(uint256 vulnId, string publicKey): For the operator to submit their public encryption key along with the attacker's rewarddecide(uint256 vulnId, bool decision): For the operator to decide on the severity of a vulnerabilityrestore(): Invoked when an operator decides to ignore a vulnerability; andexit(): Invoked when an operator decides to shut down the contract due to a vulnerability.

In the following sections, we discuss how developers will profit from implementing the Exploitable ERC standard.

0xdeface.me serves as a hub for all stakeholders (operators, attackers and contract users). We believe there is a large untapped potential for improving the security of Ethereum smart contracts by gamifying the experience. 0xdeface.me allows contract operators to confidentially negotiate with attackers, attackers to be rewarded fairly and users to be able to participate in governance decisions. By building this infrastructure, 0xdeface aims to nurture a community of security professionals by providing tools for collaboration and automation.

Now that we highlighted the main components, we will walk through the process of committing and eventually exiting a vulnerability.

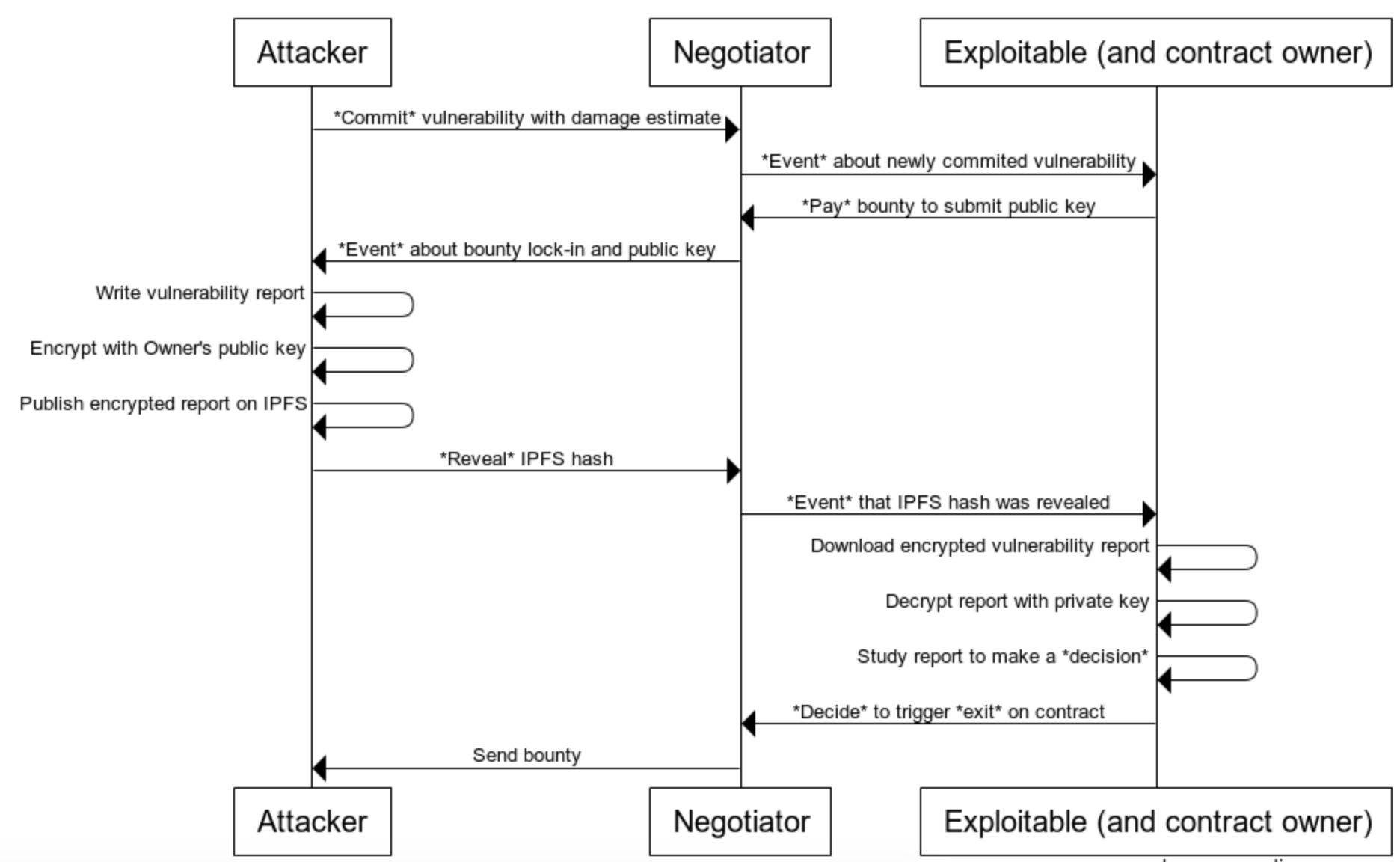

This section outlines the interactive process of commiting, paying, revealing and deciding on a vulnerability. As it serves the purpose to further understand how the system works, we're going to ignore incentives for now. Instead going to make a few assumptions to keep it simple: (1) The Exploitable contract implements the Exploitable ERC standard. (2) The attacker is willing to participate in 0xdeface's incentive game. Additionally, we're only going to describe one happy path here. We'll discuss incentives and attack vectors in one of the following sections.

As figure 1 illustrates, the process starts with the attacker finding a vulnerability in the Exploitable contract.

The attacker calls commit(IExploitable Exploitable, uint256 damage) on

the Negotiator contract. Exploitable is the vulnerable contract and

damage is the potential damage the vulnerability could cause (in "Wei").

Note that in this first iteration, we allow the attacker to set

the estimate themselves [footnote 5].

Calling commit, the Negotiator contract will make sure that IExploitable Exploitable implements implementsExploitable() and that damage doesn't

exceed the Exploitable's balance. If this is the case, a new vulnerability

will be added and a Commit(uint256 id, address Exploitable, uint256 damage, address attacker) event will be emitted to inform the contract operator [footnote

6].

At this point no information about the vulnerability has been put

online yet. The vulnerability report will be encrypted using eth-ecies

(public-key cryptography), so the contract operator must first share a public

key with the attacker [10]. This is done by the contract operator calling

pay(uint256 vulnId, string publicKey) public payable. pay checks

(1) if the vulnerability exists, (2) if an appropriate bounty was sent, and

(3) if the sender is the Exploitable contract. Is this the case, then the

vulnerability is marked paid, the public key is stored and a Pay(uint256 id, address Exploitable, uint256 bounty) event is emitted to inform the attacker.

As the contract operator's public key is now available to the attacker, the

vulnerability can be encrypted using a public key encryption scheme.

The attacker then uploads the report to IPFS and shares the hash by

calling reveal(uint256 vulnId, string hash). If (1) the vulnerability exists,

(2) the attacker has sent the vulnerability from the account that committed it,

and (3) the vulnerability was previously paid for, the hash is revealed to the

contract operator through an event Reveal(uint256 id, string hash).

Using the revealed hash, the contract operator can now download the report from

IPFS, decrypt it using their private key, and study it. They now have two

options:

(1) Decide to ignore the vulnerability and therefore send the bounty back to

themselves; or

(2) Decide to give away under the vulnerability and shut down their contract.

If they decide to give in, then the Negotiator sends the bounty to the

attacker's account.

Either way, the Negotiator emits a Decide(uint256 vulnId, bool decision) event

and closes the vulnerability.

In this section, we discussed a possible "happy path" to disclosing a vulnerability. Of course, there are many other branches. To highlight these, we discuss the incentives at play in the next section.

Earlier in this paper, claimed that 0xdeface transforms attacking smart contracts from a negative-sum game to a positive-sum game. As there are many human factors involved in the decision to maliciously drain a contract's funds, it would not make sense to outline a mathematical model of the problem here. Instead, this section argues that attackers and contract operators should use the 0xdeface protocol, and shows why this transforms attacking contracts into a positive-sum game. We make the case for why contract operators should implement the Exploitable ERC standard.

By implementing the Exploitable ERC standard, contract operators have the option to dynamically set bounties on a main net contract. While there is a cost involved in offering a bounty to attackers, it comes with several benefits: (1) It can be grown dynamically with the size of the contract's balance; (2) The contract operator's business may have changed or grown so that the vulnerability may not be the worst-case scenario for the contract operator's business anymore; (3) Shutting down and redeploying contracts becomes a canonical process; (4) Vulnerabilities are disclosed directly to the contract operator and do not end up on secondary markets instead; and (5) Investors and community are reassured that their funds are insured. In case of a shutdown, they'll likely not become angry or hesitant to invest.

Attacking smart contracts becomes a legitimate occupation, since with the Exploitable ERC standard, attackers don't have to: (1) Engage in criminal activities [footnote 7]; (2) Worry about public exposure, as they're not stealing money from investors. Rather, the protocol allows for a "Proof of Attacking", which lets attackers gain credibility and become heroes to the community rather than villains. We believe this will foster an agile hacker community, complete with quickly evolving best practices; and (3) Risk having their stolen funds blacklisted. Since bounties will be acquired legally, they can be converted to fiat and used at the receipient's discretion. We expect the most successful attackers could live on the proceeds of their legitimate security work.

Finally, users' funds are secured through the 0xdeface protocol. Since attackers will be more inclined to collect the bounty than drain the contract, user funds will not be affected by the disclosure of vulnerabilities. In addition, the Exploitable ERC standard is generic enough to allow users to vote on how to handle a vulnerability, e.g. via Aragon Agent [11]. This could make users part of the governance process in case of a imminent settlement.

The 0xdeface protocol can provide utility to users, attackers, and contract operators, and we believe this increased utility is of greater value than the increased cost of paying bounties to attackers. For this reason, the 0xdeface protocol could make contract attacking a positive-sum game.

In the next section, we'll elaborate on the potential attack vectors of the protocol and how we plan to mitigate them.

This section will list all known attack vectors and limitations of the protocol and explain how we plan to mitigate them. As more attack vectors or limitations become known, we'll update this list.

We believe we've made a compelling case for why an attacker should participate in the 0xdeface protocol. If an attacker wants to drain a contract implementing the Exploitable ERC standard anyways, they can do so. The 0xdeface protocol doesn't have a mechanism to prevent irrational actors from doing damage, but it makes it less likely that rational actors will do so.

We believe that experimentation will be necessary to find the right parameters for the 0xdeface protocol. At this point we can only speculate about the optimal ratio between a contract's balance and the 0xdeface protocol bounty. We are committed to experimenting with these parameters before launching to give contract operators reliable heuristics.

All vulnerability structs have a timeout property. If a contract operator pays

for a submitted vulnerability but the attacker never calls reveal(), a

timeout expires that allows the contract operator to reclaim the paid bounty.

A contract operator can choose to ignore a vulnerability. However, in this situation they still risk their contract being drained by an attacker.

The Exploitable ERC standard is not opinionated about the implementation of

exploitReward. A contract operator could implement an adjustable

exploitReward function that, when pay is called, could yield a smaller than

expected bounty. Attackers should always audit the Exploitable ERC

standard functions carefully to make sure they're not tricked into giving away a

vulnerability for free.

The contract operator is responsible for making sure the attacker has correctly

estimated the damage. As the damage will ultimately dictate

the bounty payout the attacker receives, the attacker might be tempted to set

the damage estimate to a higher value. If this is the case, we recommend the

contract operator to decline the vulnerability and to explain why:

string reason = "Damage value too high/low". This will allow the attacker to

submit the vulnerability again but with a correct damage estimate.

6. What if a legit vulnerability is committed but the contract operator chooses to audit the contract code themselves instead of paying the bounty?

A contract operator can choose not to pay for a submitted vulnerability,

and instead audit the code themselves. If they have enough time, they can find

the vulnerability and shut down the contract in a controlled manner.

However, we do not believe this approach is in the best interest of contract operators: (1) The contract operator risks the attacker losing patience and choosing to drain the contract illegally; (2) To execute a controlled shutdown, the operator would have to a implement a non-compliant shutdown procedure before deploying the contract. Attackers could easily spot this, and if they were suspicious they might be less likely to commit a vulnerability in the first place. The contract operator increases their risk of their contract being drained illegally if it looks like they aren't playing the game fairly; (3) If a contract operator implements a non-compliant shutdown procedure and an attacker submits a vulnerability anyway, then chooses to shut down the contract, this will attract the attention of users and other attackers. They'd be able to see that the contract operator is not playing the game fairly. We believe that in this case, the contract operator's reputation in the community would suffer significantly. Attackers may not work with them in the future, and the community may see them as being unreliable and selfish. Future attackers would be more likely to simply drain their future contracts illegally.

Even though we believe the arguments above are sufficient to stop this

behavior from happening, there are other things the protocol can help the

attackers with:

(1) The attacker can reveal their Proof of Attacking, showing to the community

that a contract operator didn't play the game fairly. We believe this would

trigger a community backlash against the contract operator in favor of the

attacker, as the community understands that good faith security research should

be fairly compensated.

(2) The attacker could choose to announce the release of the time-stamped and

unencrypted report publicly after a set time. While there may be concerns about

blackmail over forced bounty payments, this risk could pressure contract

operators into playing fair, paying attackers, and fairly exiting the contract.

(3) An attacker could encrypt a file such that it takes an estimated amount of

time on any CPU to decrypt (non-serializable computation, VDFs). An attacker

could commit a time-locked vulnerability report to the Negotiator, putting

pressure on the contract operator to make a decision within the estimated time.

To our knowledge, such encryption is unfortunately not practically possible at

this point. It is, however, a part of on-going research [11].

7. Committing vulnerabilities will motivate other attackers to audit a contract themselves and drain the contract before it is able to exit.

Malicious attackers can listen to the 0xdeface Negotiator to learn when a vulnerability has been committed against a contract, and then focus their own efforts on draining that contract. If the attacker succeeded in draining the contract illegally before the vulnerable contract exits, it would undermine legitimate attackers' efforts and defeat the purpose of the protocol. We plan to investigate Submarine Sends to prevent malicious attackers from scanning the blockchain and illegally draining committed contracts [15].

In this section, we gave an overview of the protocol's attack vectors. In the next section, we outline the limitations of the protocol.

We acknowledge that the economic incentives laid out in this document might not work as intended. In this section, we highlight some of the protocol's limitations.

Some attackers will not want to play 0xdeface's game, as there's more money to be made by simply draining a contract illegally. However, the protocol can provide an legal alternative to attackers who would prefer to act ethically and with the approval of the community.

Assume an attacker finds a vulnerable smart contract that implements the 0xdeface protocol. Instead of using the protocol, they choose to email the vulnerability report along with a demand for 1 ETH to the contract operator. While the protocol cannot prevent this behavior, we believe it would be more beneficial to both parties to work through the protocol's process: (1) The protocol makes the disclosure of vulnerabilities transparent by committing all relevant information on-chain. At any point in the process anyone can see if the contract is currently under attack, when a vulnerability was disclosed, and if a contract's exit function was called. (2) If the contract operator denies an attacker a rightfully earned bounty, the attacker can use the Proof of Attacking to confirm the legitimacy of the report. (3) Contract code is often copied and deployed by multiple independent operators (e.g. Parity's multi-sig wallet). The 0xdeface protocol makes coordinated shutdowns possible, allowing a smooth shutdown for the contract operator and a single claim for the attacker. (4) 0xdeface makes shutdowns of contracts possible in the first place. Most of the well-known contracts currently do not implement shutdown procedures. Through 0xdeface's exit function, a contract operator is invited to make a conscious decision on what to do if their contract is vulnerable even before deploying it to the network. We argue that this alone will improve overall security.

3. The exit function will not scale to a large number of users as the block gas number will be reached.

If an attacker reports a vulnerability in a contract implementing the 0xdeface protocol, and that contract has a large number (e.g. 1000) of "investors" who have ETH or tokens in the contract that would need to be refunded to the users. If the contract operator chooses to shut down the contract, the exit procedure risks hitting the Ethereum block gas limit, meaning the transaction becomes extremely expensive or fails to execute completely.

In theory, this problem could be mitigated by implementing a procedure inspired by Plasma exits. The Exploitable contract implements an exit function that sends all its ETH to a safe contract called "Claimable". The contract operator scans the original Exploitable contract for all users that have an entitlement. The contract operator builds a Merkle tree over all the scanned investor addresses and balances, then submits its root to Claimable. Now, any user with an entitlement is able to prove their outstanding balance to Claimable. By calling a function on Claimable that verifies their Merkle proof, the users can individually reclaim their ETH without having to worry about hitting the Ethereum block gas limit [14]. We are planning to investigate this scheme further.

Ultimately, only experimentation and utilization can determine if these or other limitations restrict the utility of the protocol. We are looking for funding to pay for this work.

The 0xdeface protocol is currently being built by Tim Daubenschütz and Alberto Granzotto. They are actively looking for grants to fund their work. Here are some reasons you should fund them:

Hi, I'm Tim. Since discovering Bitcoin, I've been enthusiastic about distributed systems. That's why in 2014 I joined the blockchain space as a front end developer for ascribe.io (now BigchainDB / Ocean Protocol). With ascribe, I built infrastructure for digital artists on Bitcoin. When the company shifted focus to BigchainDB, my role changed to product manager. I quickly became the central interface for internal and external developers building on BigchainDB, managing a team of ten. During that time also I had the opportunity to generalize our efforts with ascribe.io. In 2016, I co-authored COALA IP, a blockchain-ready protocol for intellectual property licensing. When BigchainDB shifted focus again in 2017, I helped prepare the company to launch their token, shadowed much of my CTO's work and helped to write the early drafts of what became the Ocean Protocol technical whitepaper. After this crazy but fun ride, I took half a year off to recalibrate myself and to recharge my batteries. As I had a lot of free time at hand I finally got to work on all the projects I had postponed over the years. In 2018, I built my own blockchain in Golang, ipfs-converter.com, mycollectibles.io, gave workshops to refugees, backpacked China and learned to play the piano. I care deeply about the future of the web, security, decentralization, open source, and permissionless innovation. Working on 0xdeface protocol would be a dream come true.

[TODO: Alberto add summary]

For inquiries email: [email protected] or meet us over a delicious Sterni anywhere in Berlin.

We're big fans of projects like Uniswap [12]. Uniswap is an Ethereum Foundation grant recipient. It doesn't require a token and comes with no artificially added cost for users. That's awesome! However, we're worried that without at a viable business model, Uniswap will eventually face funding problems.

The default settings for 0xdeface Negotiator will pay a small portion of every bounty (approx. 5%) to help fund the development and support of the 0xdeface protocol. The fee will be completely optional and users cannot or do not want to pay the fee can simply set the fee to 0, but we believe the community will choose to fund this important security work.

0xdeface is a fair and secure protocol that creates a positive-sum game by incentivizing attackers to look for vulnerabilities in Ethereum smart contracts and disclose those vulnerabilities responsibily rather than draining funds from those contracts, providing a means for contract operators to shut down vulnerable contracts, and mitigating harm to the users of those contracts.

- We expect there is a hidden community of smart contracts experts on Etherscan's "Verified Contracts" page. We hope to legitimize this community and give it a home at 0xdeface.me.

- Ethereum smart contracts will be changeable in-place with the Constantinople update in February and the introduction of CREATE2.

- We are not currently aware of criminal cases against smart contract attackers, but it is just a matter of time before such cases are brought. Attacks of this nature are plainly illegal, as previous cases about the theft of digital goods have shown [7].

- Even though Gnosis's DAOStack contracts were audited before being deployed to the Ethereum main net, these contracts were drained as part of their extended bounty program within hours [3].

- We acknowledge that setting

damageto an incorrect value could potentially lead to an attack vector, where the attacker overstates the criticality of a vulnerability's damage. It would be the responsibility of the contract operator to do the math on the vulnerability. If they decide to decline a legitimate vulnerability because of an overstateddamageestimate, thedecide'sstring reasonbe used to explain the decision. - 0xdeface plans to deploy an Ethereum blockchain listener that contract operators can subscribe to via email for updates on the latest emitted events.

- The 0xdeface protocol is completely voluntary and consensual as only contracts implementing the Exploitable ERC standard can be attacked.

- PEREZ, Daniel; LIVSHITS, Benjamin. Smart Contract Vulnerabilities: Does Anyone Care?. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.06710, 2019.

- https://medium.com/@ogucluturk/the-dao-hack-explained-unfortunate-take-off-of-smart-contracts-2bd8c8db3562

- https://blog.gnosis.pm/security-update-on-the-dxdao-bug-bounty-52cec0f02cde

- https://github.com/ConsenSys/mythril-classic

- https://github.com/trailofbits

- https://etherscan.io/contractsVerified

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/video-games/9053870/Online-game-theft-earns-real-world-conviction.html

- https://hackerone.com/augurproject

- https://twitter.com/mythril_watch

- https://uniswap.io/

- https://www.gwern.net/Self-decrypting-files

- https://blog.zeppelin.solutions/on-the-parity-wallet-multisig-hack-405a8c12e8f7

- https://pdaian.com/blog/solidity-anti-patterns-fun-with-inheritance-dag-abuse/

- https://github.com/leapdao/merkle-mine-contracts/blob/master/SPEC.md

- https://libsubmarine.org/