Uses a combination of Vertical Slice and Clean architecture.

Vertical Slice - to structure all logic of a use case.

Clean - to compartment-ize common execution of code in a layered manner.

Low coupling; high cohesion

Folders and namespaces is the first level of understanding how an application works

We separate what's shared and what is commonly run amongst all our code

All our business logics are grouped as features/use cases/activities.

We remove the concern and dependencies of code infrastructure from the business use cases.

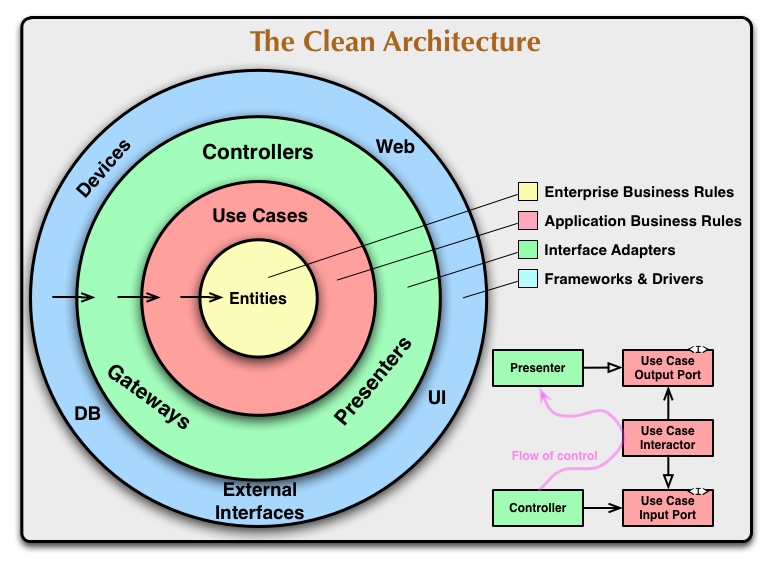

We follow the core idea from Clean Architecture where it states:

Source code dependencies can only point inwards.

What this means that the logic within a certain layer will not be exposed to another layer and only can it communicate to its adjacent inner layer through an interface it defines.

But this goes as far to describe how we decouple concerns and not how we manage a highly cohesive understanding of what our application does.

This is where Vertical Slice Architecture comes into play.

Encapsulating and grouping all concerns from front-end to back. Remove the gates and barriers across those layers, and couple along the axis of change.

Vertical slice shifts our mindset to focusing on the domain space than technical challenges. It puts the use cases first and foremost which is evident by the way we structure and present code.

Businesses regularly put too much effort into developing glorified database table editors.. CRUD systems can't produce a refined business model by only capturing data.

- Implementing Domain-Driven Design, pg. 172-172

Using the principles of clean architecture we integrate the pieces we need to make a feature work and gather them under the same umbrella with less ceremonies and abstraction.

Talking about abstractions - because our code is now strongly cohesive and decoupled from the concerns of other features, we can remove all the abstractions such as dto or adaptor services.

We choose pragmatism over dogmatism. Write code that allows us to read quickly. Less code to manage. Minimal jumping around. Add abstract only when it stops us from extending our code sanely.

Some thoughts on when to abstract:

- When we are continuously making the same change in different use cases, abstract the coupled behaviour into a common service.

- When part of the code is worked by someone else, we can split that out so that we can work in parallel. The "black box" effect provided by abstraction helps developers work in isolation through its ubiquitous API.

Some important terms to know when reading this:

- Layers: when we mention layers we are talking about layers in a clean architecture sense.

- Use Cases: when we mention use cases we are talking about use cases in a vertical slice concept. Also known as features.

- Aggregate root: the terminology used in Domain Driven Design. Aggregate root is a cluster of associated objects that we treat as a unit for the purpose of data changes.

To provide some guidelines to where code should exist, we will break them down into three categories (or layers):

- Use case - All code and its layers specific to a vertical slice.

- Broker - Adapters, SDK or code that we use to connect to an external data source. Have a read on what The Standard says about it. e.g: third-party API, repository patterns, email services, notification services, etc.

- Infrastructure - Albeit each use case has its own layers, there will be shared/common infrastructure; this is where it ends up.

Continuing on are more in-depth explanation of each category.

Do note from one language to another the structures may look slightly different. But the core concepts are the same and may be called slightly differently to suit the conventions of the particular language.

All the work we do solves a use case that we have for our product. How consumers interact with our application, how we validate that interaction and how we handle that with business logic.

- All work are co-located to ease navigation between code and understandable at a glance.

- All business logic (user interface, DTOs, validations, persistent interaction, business domain smarts, and responses) are all in the same namespace and folder.

- All code to be isolated to its own use case so that when it is refactored or tempered it will not affect another use case.

- This may feel like a smell once you see duplicate code all over the place - that's fine; We focus on the right abstraction rather than DRY-all-the-things

- When then to abstract? When you're clear the rules governing both duplications are strictly identical and aligned.

- Each use case can work differently (ie one may be a http only endpoint another could be a messagint endpoint)

- Route

- This is the entry point into our use case. Some maybe a HTTP endpoint, event subscriber or just a serverless trigger.

- In the Clean Architecture this would be the

controller. The interface into the actual work we are to do. - There should be no business logic here whatsover.

- The most would be information or metadata about the controller, such as: Does it have authorization? What kind of request does it take? How should it respond to the user?

- Each use case should only have a single route but multiple types: ie one could be a HTTP method and the other a GRPC method.

- Its requests and responses of the route are to be declared here. The most it could have are validation metadata on the requests.

- The requests should be mapped into a DTO when there are different modes of controllers that has different transform from request to our handler's command.

- Handler

- The crux of the interaction between the request and the domain logic.

- In the Clean Architecture this would be the

applicationlayer. The one that orchestrates the business domain work. - The handler should only be dealing with abstract data types.

- It understands how to inject in the layers above it, such as any broker or the DTO from

Route. - As well this will the touch point where we then send the data back to the

Route.

- Data Access & Domain

- These two components plays apart in maintaining our state

- This follows two ideas: (1) Domain Driven Design and (2) Seperation of concern of data access and logic.

- Code only to the use case and nothing more

- Caveat: Not all situation will need a domain(business logic). This is more often, than not, in queries. IMO, the query logic can all be done within the data access area.

- You may ask "Why do you still have data access code here? That's not clean". Answer:

- We follow a more pragmatic approach; end of the day all this is our code,

- more abstraction and layers adds more complexity,

- and this follows close to the vertical slice architecture.

- Data Access

- Every use case requires access to a set of data so ever differently

- This is where we gather all the brokers we need to interact with.

- Here we can piece together the aggregates that we need to form our domain.

- Think about it as our Aggregate factory or Repository.

- The data access should generate our domain and understand how to update our persistent layer with the mutated domain.

- If data must be accessible within the Domain, due to the nature on how an external API interacts with the state change, we can use delegate lambdas to abstract just that interaction. (See this post;although written in Ruby it does a good job explaining this concept)

- Domain

Domainis our aggregate root for this use case- In the Clean Architecture this would be the

entity. - This should be the only place we can change the state.

- There should be, dare say, no dependencies here.

- When we deal with plain objects, it helps us to test the domain logic easily for edge cases and multiple cases.

- Hence, this should not have dependencies on any other services/brokers. Stay away from "God objects".

- "What if i need a function from say a time calculator?". Answer:

- Use an interface onto your domain method's argument. The IOC will then be the

handler. - Think of this as a pure function of inputs and outputs (albeit the output is the domain object itself).

- Use an interface onto your domain method's argument. The IOC will then be the

Brokers are a liaison between business logic and the outside world. They are wrappers around external libraries, resources, services, or APIs to satisfy a local interface for the business to interact with them

- There should be no business logic here.

- They should be as thin as possible; just a wrapper around our code.

- At most a mapper from the external API into an internal interface that we can work with

- The interface should be generic and as known and understood as time itself. For instance if it is a CRUD API, we should only have get, post, delete methods. How those APIs are called are totally unknown to the consumers of the broker.

These are the layers outside of our domain. Infrastructure that runs our domain logic through the layers. This follows loosely on the clean architecture.

Not always code are directly related to our uses cases but more so to make the framework work for our application. This is where such code resides.

Code that are needed for the framework and not dependent to the core of the feature.

Through dependency injection, they can be used by the inner layer that resides in our use case.

Think of it this way, if we remove this code does it impede the essence and goal of our use case?

Such code would be:

- logging

- authorization and authentication breakdowns

- atomic transaction commits

- general request enrichment

- system-wide mandates (such as auditing or event publishing)

Currently using github actions (.github/). The principles here are:

- split the pull request and deployment into different processes.

- allow CICD to operate using ship-show-ask

- Borrows ideas from https://github.com/threenine/api-template

- Understanding how to layout your folders from Architecture the Lost Years by Robert Martin

- How to do vertical slice architecture by Jimmy Bogard

- Some principles on how to think about domain/business logic from John P Smith