This tutorial is based on nmt-typs tutorial (for dynet lamtram toolkit) by Graham Neubig and will explain some practical tips about how to train a neural machine translation system. It is partly based around examples using the OpenNMT-py toolkit. Note that this will not cover the theory behind NMT in detail, nor is it a survey meant to cover all the work on neural MT, but it will show you how to use OpenNMT-py in more details, and also demonstrate some things that you have to do in order to make a system that actually works well.

Encoder-decoder models are the simplest version of NMT. The idea is relatively simple: we read in the words of a target sentence one-by-one using a recurrent neural network, then predict the words in the target sentence.

First, we encode the source sentence. To do so, we convert the source word into a fixed-length word representation.

Then, we map this into a hidden state using a recurrent neural network.

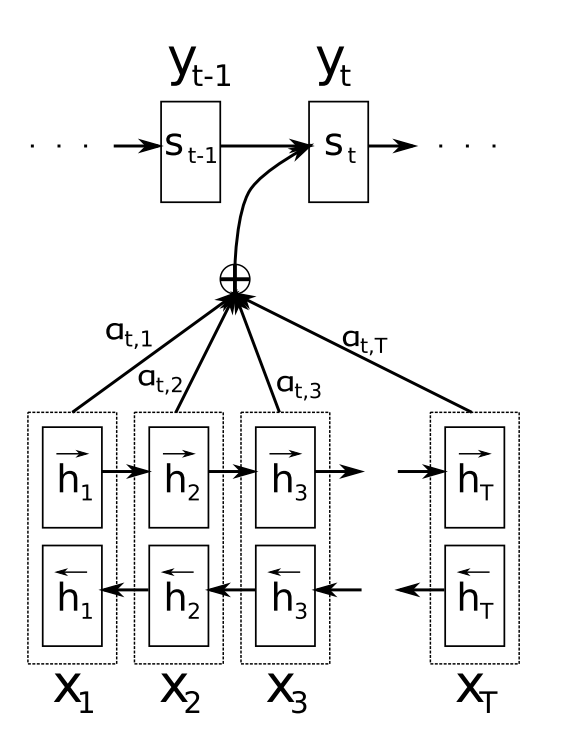

It is also common to generate hidden states using bidirectional neural networks, where we run one forward RNN that reads from left-to-right, and another backward RNN that reads from right to left, then concatenate the representations for each word. This is the default setting in OpenNMT-py (specified by -brnn option at train.y script). You can also choose a merge action for for the bidirectional hidden states (specified by -brnn_merge [concat|sum]).

The picture below (from Bahdanau et al.) shows how does bidirectional encoder looks like.

Bidirectional encoder as a part of encoder-decoder architecture

You can also use other encoder architecture using -encoder_type parameter. Choices are ['rnn', 'brnn', 'mean', 'transformer', 'cnn'].

Next, we decode to generate the target sentence, one word at a time. This is done by initializing the first hidden state of the decoder to be equal to the last hidden state of the encoder. Next, we generate a word in the output by performing a softmax over the target vocabulary to predict the probability of each word in the output.

You can also use other decoder layer architecture using -decoder_type parameter. Choices are ['rnn', 'transformer', 'cnn'].

However, there are also some specific arguments for transformer and cnn architectures. It is more relevant to Improving NMT stage we will have later in the course.

You can choose number of layers in encoder and decoder using -enc_layers and -dec_layers options.

We can also specify number of units for the RNN with -rnn_size option.

To change type of the RNN Gate use -rnn_type parameter (choices are ['LSTM', 'GRU', 'SRU']).

We then update the hidden state with this predicted value.

This process is continued until a special "end of sentence" symbol is chosen.

The standard way we do training is through stochastic gradient descent (SGD), where we calculate the gradient for a single example then update the parameters based on an update rule. If we go through all the training examples, we say that we go trhough one epoch. You can use -epochs parameter to specify for how much epochs at max you want to train your model.

If training is going well, we will be able to see something similar to this as our output:

Epoch 1 sent 100: ppl=1122.071, time=2.04832 (502.852 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 200: ppl=737.811, time=4.08551 (500.305 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 300: ppl=570.027, time=6.07408 (501.311 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 400: ppl=523.924, time=8.23374 (502.566 w/s)

ppl is reporting perplexity on the dev set (in case of OpenNMT-py; other frameworks might report trainig set ppl).

For this perplexity, lower is better, so if it's decreasing we're learning something.

But if you update using one example per time, you will notice that training is really slow... The next section will explain how we speed things up.

One powerful tool to speed up training of neural networks is mini-batching. The idea behind minibatching is that instead of calculating the gradient for a single example we calculate the gradients for multiple examples at one time then perform the update of the model's parameters using this aggregated gradient. This has several advantages:

- Gradient updates take time, so if we have N sentences in our minibatch, we can perform N times fewer gradient updates.

- More importantly, by sticking sentences together in a batch, we can share some of the calculations between them.

- Also, using mini-batches can make the updates to the parameters more stable, as information from multiple sentences is considered at one time.

On the other hand, large minibatches do have disadvantages:

- If our mini-batch sizes are too big, sometimes we may run out of memory by trying to store too many calculated values in memory at once.

- While the calculation of each sentence becomes faster, because the total number of updates is fewer, sometimes training can be slower than when not using mini-batches.

Anyway, let's try this in OpenNMT-py by adding the -batch_size and-max_generator_batches NUM_WORDS option, where NUM_WORDS is the number of words included in each mini-batch. If we set NUM_WORDS to be equal to 256, and re-run the previous command, we get the following log:

Epoch 1 sent 106: ppl=3970.52, time=0.526336 (2107.02 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 201: ppl=2645.1, time=1.00862 (2071.15 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 316: ppl=1905.16, time=1.48682 (2068.84 w/s)

Epoch 1 sent 401: ppl=1574.61, time=1.82187 (2064.91 w/s)

Looking at the w/s (words per second) on the right side of the log, we can see that we're processing data 4 times faster than before, nice!

In addition to the standard SGD_UPDATE rule listed above, there are a myriad of additional ways to update the parameters, including "SGD With Momentum", "Adagrad", "Adadelta", "Adam", and many others. Explaining these in detail is beyond the scope of this tutorial, but it suffices to say that these will more quickly find a good place in parameter space than the standard method above. Most common optimization method nowadays is "Adam". Use -optim parameter to choose optimazer, and -learning_rate to set up the learning rate. Note, that for different optimizers differnet learning rates are better on practice.

You can also use -learning_rate_decay stategy

If you rerun train.py with SGD, you'll probably find that the perplexity drops significantly faster than when using the standard SGD update (after the first epoch, one might have a perplexity of 287 with standard SGD, and 233 with Adam).

One of the major advances in NMT has been the introduction of attention. The basic idea behind attention is that when we want to generate a particular target word, that we will want to focus on a particular source word, or a couple words. In order to express this, attention calculates a "context vector" that is used as input to the softmax in addition to the decoder state.

This context vector is defined as the sum of the input sequence vectors, weighted by an attention vector.

OpenNMT-py uses attention by default.

There are several ways to calculate the attention scores. The following ones are implemented in OpenNMT-py, and can be changed using the -global_attention TYPE option. Choices are ['dot', 'general', 'mlp'].

We use test set to see how well our model is able to generalize to new examples. We employ BLEU metric to get some score.

The first problem that we have to tackle is that currently the model has no way of handling unknown words that don't exist in the training data. A year or two ago, most common way of fixing this problem was by replacing some of the words in the training data with a special <unk> symbol, which will also be used when we observe an unknown word in the testing data.

However, nowadays, it is easy solved with BPE.

The second problem, over-fitting, can be fixed somewhat by using a development set. The development set is a set of data separate from the training and test sets that we use to measure how well the model is generalizing during training. There are two simple ways to help use this set to prevent overfitting.

The first way we can prevent overfitting is regularly measure the accuracy on the development data, and stop training when we get the model that has the best accuracy on this data set. This is called "early stopping" and used in most neural network models.

OpenNMT-py oututs dev set perplexity by default, so we can see when it reaches suitable minimum to stop training early.

You have probably noticed how every pass over the training data, we're measuring the perplexity on the development set.

It is controlled by -learning_rate_decay. We mentioned this parameter before. This reduces the learning rate γ every time the perplexity gets worse on the development set. This causes the model to update the parameters a bit more conservatively, which as an effect of controlling overfitting.

In the initial explanation of NMT, it was explained that translations are generated by selecting the next word in the target sentence that maximizes the probability. However, while this gives us a locally optimal decision about the next word, this is a greedy search method that won't necessarily give us the sentence that maximizes the translation probability.

To improve search (and hopefully translation accuracy), we can use "beam search," which instead of considering the one best next word, considers the k best hypotheses at every time step. If k is bigger, search will be more accurate but slower. k can be set with the -beam_size BEAM option during decoding.

where we replace the two instances of BEAM above with values such as 1, 2, 3, 5.

The results might look like

BEAM=1: BLEU = 8.83, 42.2/14.3/5.5/2.1 (BP=0.973, ratio=0.973, hyp_len=4564, ref_len=4690)

BEAM=2: BLEU = 9.23, 45.4/16.2/6.4/2.5 (BP=0.887, ratio=0.893, hyp_len=4186, ref_len=4690)

BEAM=3: BLEU = 9.66, 49.4/18.0/7.5/3.1 (BP=0.805, ratio=0.822, hyp_len=3855, ref_len=4690)

BEAM=5: BLEU = 9.66, 50.7/18.7/8.0/3.4 (BP=0.765, ratio=0.788, hyp_len=3698, ref_len=4690)

BEAM=10: BLEU = 9.73, 51.7/19.2/8.5/3.8 (BP=0.726, ratio=0.758, hyp_len=3553, ref_len=4690)

we can see that by increasing the beam size, we can get a decent improvement in BLEU.

Lets now open OpenNMT-py soruces and see what exact model have we actualy train (by looking at default parameters).