-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 65

Isotropic Remeshing

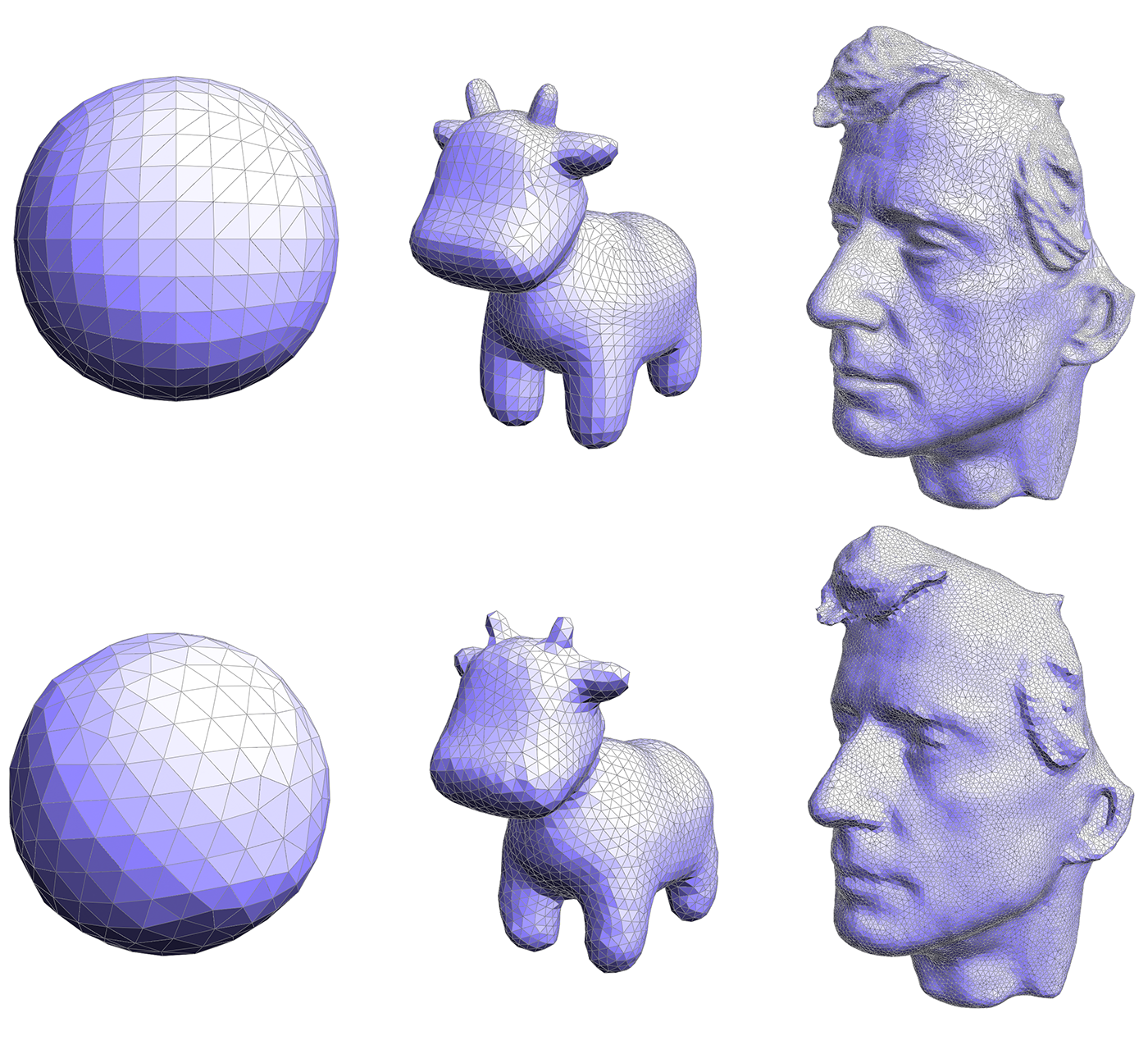

Scotty3D also supports remeshing which keeps the number of samples roughly the same, while improving the shape of individual triangles. The isotropic remeshing algorithm tries to make the mesh as "uniform" as possible, i.e., triangles as close as possible to equilateral triangles of equal size, and vertex degrees as close as possible to 6 (note: this algorithm is for triangle meshes only). The algorithm to be implemented is based on the paper Botsch and Kobbelt, "A Remeshing Approach to Multiresolution Modeling" (Section 4), and can be summarized in just a few simple steps:

- If an edge is too long, split it.

- If an edge is too short, collapse it.

- If flipping an edge improves the degree of neighboring vertices, flip it.

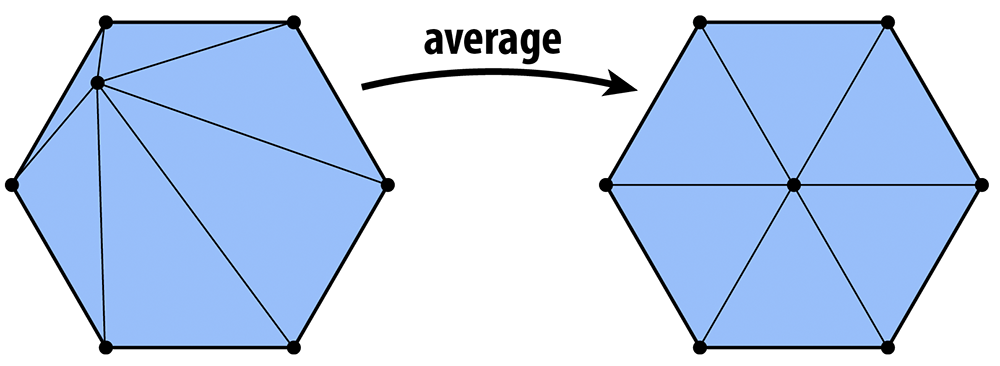

- Move vertices toward the average of their neighbors.

Repeating this simple process several times typically produces a mesh with fairly uniform triangle areas, angles, and vertex degrees. However, each of the steps deserves slightly more explanation.

Ultimately we want all of our triangles to be about the same size, which means we want edges to all have roughly the same length. As suggested in the paper by Botsch and Kobbelt, we will aim to keep our edges no longer than 4/3rds of the mean edge length L in the input mesh, and no shorter than 4/5ths of L. In other words, if an edge is longer than 4L/3, split it; if it is shorter than 4L/5, collapse it. We recommend performing all of the splits first, then doing all of the collapses (though as usual, you should be careful to think about when and how mesh elements are being allocated/deallocated).

We want to flip an edge any time it reduces the total deviation from regular degree (degree 6). In particular, let a1, a2 be the degrees of an edge that we're thinking about flipping, and let b1, b2 be the degrees of the two vertices across from this edge. The total deviation in the initial configuration is |a1-6| + |a2-6| + |b1-6| + |b2-6|. You should be able to easily compute the deviation after the edge flip without actually performing the edge flip; if this number decreases, then the edge flip should be performed. We recommend flipping all edges in a single pass, after the edge collapse step.

Finally, we also want to optimize the geometry of the vertices. A very simple heuristic is that a mesh will have reasonably well-shaped elements if each vertex is located at the center of its neighbors. To keep your code clean and simple, we ask that you implement the method Vertex::computeCentroid() which should compute the average position of the neighbors and store it in the member Vertex::centroid. The reason this value must be stored in a temporary variable and not immediately used to replace the current position is similar to the reason we stored temporary vertex positions in our subdivision scheme: we don't want to be taking averages of vertices that have already been averaged. Doing so can yield some bizarre behavior that depends on the order in which vertices are traversed (if you're interested in learning more about this issue, Google around for the terms "Jacobi iterations" and "Gauss-Seidel). So, the code should (i) first compute the centroid for all vertices, and (ii) then update the vertices with new positions.

How exactly should the positions be updated? One idea is to simply replace each vertex position with its centroid. We can make the algorithm slightly more stable by moving gently toward the centroid, rather than immediately snapping the vertex to the center. For instance, if p is the original vertex position and c is the centroid, we might compute the new vertex position as q = p + w(c - p) where w is some weighting factor between 0 and 1 (we use 1/5 in the examples below). In other words, we start out at p and move a little bit in the update direction v = c - p.

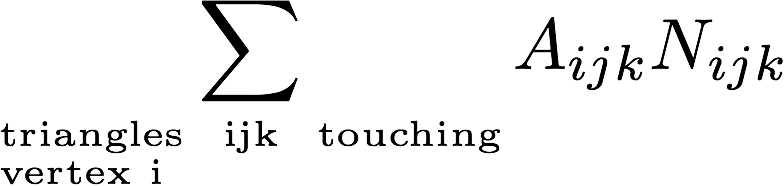

Another important issue arises if the update direction v has a large normal component, then we'll end up pushing the surface in or out, rather than just sliding our sample points around on the surface. As a result, the shape of the surface will change much more than we'd like (try it!). To ameliorate this issue, we will move the vertex only in the tangent direction, which we can do by projecting out the normal component, i.e., by replacing v with v - dot(N,v)N, where N is the unit normal at the vertex. To get this normal, you will implement the method Vertex::normal(), which computes the vertex normal as the area-weighted average of the incident triangle normals. In other words, at a vertex i the normal points in the direction

where A_ijk is the area of triangle ijk, and N_ijk is its unit normal; this quantity can be computed directly by just taking the cross product of two of the triangle's edge vectors (properly oriented).

The final implementation requires very little information beyond the description above; the basic recipe is:

- Compute the mean edge length L of the input.

- Split all edges that are longer than 4L/3.

- Collapse all edges that are shorter than 4L/5.

- Flip all edges that decrease the total deviation from degree 6.

- Compute the centroids for all the vertices.

- Move each vertex in the tangent direction toward its centroid.

Repeating this procedure about 5 or 6 times should yield results like the ones seen below; you may want to repeat the smoothing step 10-20 times for each "outer" iteration.

- Task 1: Camera Rays

- Task 2: Intersecting Primitives

- Task 3: BVH

- Task 4: Shadow Rays

- Task 5: Path Tracing

- Task 6: Materials

- Task 7: Environment Light

Notes:

- Task 1: Spline Interpolation

- Task 2: Skeleton Kinematics

- Task 3: Linear Blend Skinning

- Task 4: Physical Simulation

Notes: